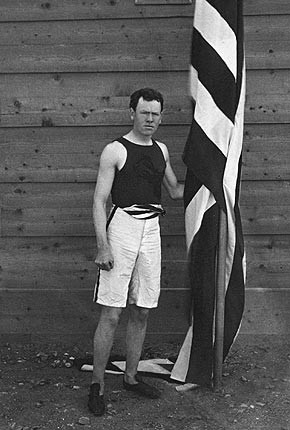

First-place medallist James Connolly, Athens, 1896. (Photo credit: IOC Olympic Museum) |

James Brendan Connolly was a passenger aboard the RMS Republic when she was hit by the inbound immigrant ship S.S. Florida in the early morning hours of January 23, 1909. Did the Republic sink with her lengendary treasure in Czarist gold? Connolly, a prolific writer of sea stories, thought any gold was removed. But, visit our homepage, The Official RMS Republic Website and make your own decision. At the first modern Olympic games held in Athens, Greece, in 1896, James Brendan Connolly won the gold medal (actually, silver medals were then awarded for first place) in the triple jump despite the fact that the triple jump in Athens was two hops and a jump rather than the hop, skip, and jump for which Connolly had trained and was the American champion. He threw his cap a yard beyond the mark set by his main competitor and then managed to leap even beyond the cap, just short of 13.5 meters, a mark that was short of his personal best and also of the world record he would set later that year. It was the first first-place medal awarded in modern Olympic history. Connolly also won second place in the high jump and third place in the long jump.

TRIVIA QUESTION: James Brendan Connolly of the United States won the first medal of the 1896 Olympic Games in what event? ANSWER: Connolly took first place in the triple jump. According to Connolly, he describes the event as "the triple-saute," then also known as the "Hop, Step and Jump or Two Hops and Jump." "The program was in French." See: The First Olympic Champion. |

|

| |

Ralph C Wilcox

The University of Memphis, USA

James Brendan Connolly, a writer of sea stories and winner of the first title for the United States in the first modern Olympic Games, died today in the Veteran's Administration Hospital at Jamaica Plain. He was 88 years old.2

So began an obituary in The New York Times of January 21, 1957. Born one of twelve children to Irish-Catholic parents, John and Ann (O'Donnell) Connolly, in South Boston, on October 28, 1868, his father was a fisherman out of T wharf on the city's waterfront. Later described as a "gentleman adventurer" in the mould of Kipling, James Brendan Connolly is perhaps best remembered as America's foremost writer of maritime tales. He authored 25 full-length works and more than 200 contributions to a variety of newspapers and journals.3 He fought with the Ninth Massachusetts Infantry at San Juan Hill during the Spanish-American War, that is the Irish Fighting Ninth of Civil War fame, was granted a private audience with Pope Pius X, in Rome, in 1911, ran for the US Congress on the Progressive Party ticket in 1912 and again in 19144 and later served as Commissioner, in Ireland, for the American Committee for Relief in Ireland in which capacity he regularly fraternized with gunmen of the Irish Republican Army.5 However, it is a lesser-known chapter of Connolly's life upon which this study focuses.

The nature and function of sport in American society have both undergone constant change throughout the past century. To fully understand the emergent structure and significance of contemporary sport demands an appreciation of its development over time that is, the process of modernization. The purpose of this study is to examine the role of sport in the life of James Brendan Connolly through identifying those individuals and institutions that early influenced his athletic career. Further, this study will explore the impact of the sporting life on the formulation of that clear system of values and ideals embraced by the author and promulgated throughout his literary works. Moreover, this study seeks to better understand Connolly's views on the rapidly changing nature of American sport and to evaluate the extent of his influence on the expanding bureaucracy and practice of sport throughout the early decades of the twentieth century. In effect, this study utilizes Connolly's contemporary assessment to test the validity of a variety of paradigms that have been put forward to explain the modernization of American sport.6

Sport and Urbanization: City, Community, and Self-Identity

In his later years Connolly shared, with great pride, stories of his upbringing in the predominantly Irish-Catholic neighbourhood of South Boston. It was here, Connolly wrote, that he was first inducted into the bachelor sub-culture of the sporting life,

In the... district of the city where I was born and brought up most of all the men were interested in an athletic sport of some kind. Most of the older people of the district were of high blood still keen for the field sports of the old country. You could find the old men unable to read or write [but] could argue keenly, intelligently on any out door sport whatsoever. And among those old men were many who had been themselves athletes of fame; hurlers, bowlers, wrestlers,...

The physical standard of the district was high; so, likewise, me, the moral standard; and I say that with a full appreciation of the fact that a policeman's lot was never a happy one...

They were a hot-blooded fighting lot; but also a clean-living, sane and healthy lot... the children growing up healthy, rugged just naturally had a taste for athletics. Among the boys I knew as a boy it was the exception to find one who could not run or jump or swim... or play a good game of ball...

Among a people of gifted and mostly too poor to afford more than a grammar school education,... there is to be a good number who will take some occupation whereto their physical gifts will not be wasted. Many of them went in for professional athletics. Within half a mile of where we lived when I was a schoolboy, were six major league players... the players of record... champions of the day... the district took their excellence as a matter of course...7

Connolly retained strong ties to the neighborhood in which he was raised. During his campaign for Congress in 1914, he resurrected his vehement reaction to a criticism of South Boston which had earlier appeared in an editorial in the Boston Herald by offering the following testimony,

I was born and brought up in South Boston and until a few years ago, had my residence there. I have dwelt elsewhere, probably in as many different communities, and have possibly known as many different kinds of people as most men of my years, and will you believe me when I say that South Boston is the most moral large community I know anything of? And further, if I were to be born over again, I would rather be born in South Boston, than any other place I know of by that I mean to say that I would be more nearly in the way of preserving my mental, physical and spiritual faculties from degenerating.8

Within the close-knit community of South Boston, local sporting heroes figured prominently in young Connolly's life. Among them was John L. Sullivan the "Boston Strong Boy" and world heavyweight boxing champion (1882-1892), who Connolly recalled walking up to in the street, on a regular basis, "`Hello John' I used to shout. `Hello kid!' He didn't know me but he never quizzed me [for I was] a boy that had a right to salute him familiarly a boy of the district."9 Yet it is to a neighbor by the name of Gallohue, who enjoyed fame as a circus acrobat, that Connolly attrib uted his earliest interest in track and field. To the local boys "Our curious jumper, of whom we were all very proud [he wrote], was a true picture of an athlete, six feet in height and weighing 190 lbs stripped..." On one occasion when Gallohue came home dressed in a superb new suit, Connolly added, "It cost 60 dollars, a lot of money for a suit of clothes then in our district at least," the payoff of a bet made by the circus manager "that he couldn't jump over a baby elephant".10

Growing up at a time when the parks and playground movement in Boston was slowly developing, Connolly joined other boys in the streets and vacant lots to run, jump, and play ball. Yet public tolerance of juvenile play was limited as Connolly remembered, "When we got bigger and tried it the police would stop us; that drove us onto what used to be called the State Flats."11 Situated between South Boston and the harbor, the State Flats represented a 40-50 acre parcel of reclaimed land composed of clay deposits dredged from the bottom of Boston harbor. Laying adjacent to the central railroad yards of the city, the sunbaked clay track of the State Flats early became a training venue for many of the city's premier athletes. Connolly continued, "It was the professional athletes who were our own role models; the best in the country came there. In those days the Scotch and Irish societies used to run great [festivals] in Summer. The big drawing cards ... were the professional athletic games."12 In an unfinished short story, entitled "The Piper", Connolly elaborated upon the world of the professional runner. Written as a tribute to Piper Donovan, the author recalled,

We had schools of professional running then, not one but many. Every shoe town, every other mill town had its champion... There was money in the game then... Towns would go broke backing their man. Those men had experiences that would read like stirring fiction and that without embellishment.13

Later, in May of 1896, Connolly found himself being lauded as a hero of the neighborhood. Presented with a gold watch, at an official banquet given by the City of Boston in Faneuil Hall, the first modern Olympic victor was to be most noticeably touched by the citizens of South Boston who staged a parade on his behalf. Connolly remembered,

...with many carriages and a double line of policemen from curb to curb, to clear the way... with red and blue and green lights and sky rockets flaring up from in front of drug stores, clothing stores, private homes and barrooms and the band all the while playing "See the Conquering Hero Comes!"... The procession halted and we filed up to a hall...14

Earlier, after completing his education first at Notre Dame Academy and then at the Mather and Lawrence grammar schools of his district, Connolly had spent time as a clerk with an insurance company in Boston and later with the U.S. Corps of Engineers in Savannah, Georgia. His predisposition to sport, and his impact on the community, soon became apparent. Calling a special meeting of the Catholic Library Association (CLA) of Savannah in 1891, he was instrumental in forming a football team. In a letter to Julian R. Leane, the business manager of the University of Georgia Football Team Connolly, by this time identified as the Captain of the new team, actively pursued a meeting between the two teams adding,

Our team is generally admitted to be the strongest in this section, while yours easily leads the rest of the state...

Among our members can be found some of the most enthusiastic amateur athletes in the South. We do not tolerate professionalism... We will guarantee you sufficient expense to relieve you from apprehensions on that score...

The letter includes the names of the CLA eleven that played the YMCA in an earlier game. Furnished, "In order to satisfy [The University of Georgia] that the personnel of our team is not objectionable", the list included attorneys, bankers, retailers, clerks and an undertaker.15 In a subsequent letter, Connolly responded to Leane's request for technical guidance in establishing a personal training regimen for track and field. In a detailed, and illustrated, nine-page letter, a young yet clearly assertive Connolly advised,

Practice easily but regularly. Overtraining is worse than undertraining. After exercise a cold quick sponge bath and rough towel rubbing... Eat any plain food you like,... Drink a little liquid as you can during the day of a race, outside of your usual allowance of tea or coffee... Do not run the day before a race... From 4 to 5 in the afternoon is the best time to exercise and about five times a week usually gives best results.16

Connolly's early correspondence from Savannah also provides an insight into his lifelong resolve to challenge inaccurate or slanderous allegations directed his way by newspaper editors and others.17 In an eight-page letter to the editor of the Atlanta Journal in 1892, Connolly questioned the newspaper's propriety in publishing an unsubstantiated response to the CLA football team's earlier, and more widely published claims of "bluffing tactics" used by the Atlanta team to avoid a promised game. Supported by painstaking documentation, including the text of six telegrams, Connolly's case concluded with the following challenge,

First. The CLA Team of Savh. will play the Atlanta team in Savannah and allow them $250 for expenses. After deducting receipts to be divided equally between two clubs. The loser to pay the cost of a trophy not to exceed $150 in value to be selected by the winner. If the Atlanta Team will allow the CLA the same privileges we will play them in Atlanta. If the game takes place in Atlanta the CLA team to have the selection of both referee and umpire, one man to be taken from each city. If the game takes place in Savannah we will allow Atlanta choice of both men one from each city.

Second. The CLA Team will play in neutral ground, Macon for instance: each team to pay its own expenses. The winner to take half and the loser half of the net receipts, but the losers shall purchase with their entire receipts a trophy to be selected by the winner. Each team to select one man, to act for them as Referee and Umpire respectively.

Third. If the Atlanta Team will make a submit proposition giving conditions under which they will play us, I will now bind our team to play provided that I am allowed to take for my team any privileges that you propose to serve yourselves.18

A little over one month later, a letter to the Editor of the Macon News found Connolly addressing allegations that his team had, with the utmost reluctance, agreed to play the Mercer College Football Team on March 16, 1892, and that CLA players included "members of the Hebrew Association, hired professionals, and day laborers of Savannah." Characterized as "a willful distortion of the real truth" by Connolly, he embarked upon a seven-page defense which was subsequently published in the Macon News. Notable, is his emotional attack on earlier questions raised by the newspaper against his teammate Mr. Coningham on the basis that "he worked with his hands for a living". Such blue-blooded arrogance, so clear to one that had grown up in South Boston, would remain irksome to Connolly throughout his life.19 Yet Connolly's measured, egalitarian response to the Macon News stood in stark contrast to an eight-page letter that he sent to the captain of the Mercer College Football Team three days later in which he more humbly explained, "Our membership here is composed of all classes of people, wealthy and poor, Christian and non-Christian." Apparently sensing a deeper need to explain the appearance of Mr. Myers on the CLA team, Connolly wrote, "All of the team are not Catholics... They pay the same dues that their Catholic brethren pay and are treated with the same consideration" and, falling into the trap of ethnic stereotyping himself, added,

We didn't expect to have to use him and with due regard to Mr. Myers' exceeding cleverness we could have used other men to better advantage than him, for his weight barely exceeds 145 lbs. Mr. Myers is not connected in the remotest way with Mr. Gus Meyer, a professional pugilist from New York who spends his winters in Savannah giving sparring lessons. Our Mr. Myers (Fred) moves in the highest social circles here... is a member of the Young Men's Hebrew Assn., but did not play with their team.

Seeking to solidify his case beyond any reasonable doubt, Connolly leveled specific charges of unsportsmanlike practice at the opposition, including unprovoked violence on the part of the Mercer players; attacks on CLA players by spectators; attempts to recruit non-student players to the college team; spying on the CLA team practice two weeks before the game; non-student spectators being admitted at half-price; substitutions without notification during the game; and the feigning of injury.20

Connolly had early become a central figure in the Savannah sporting community. He was paid five dollars a week to write a sports column for a local weekly called the Lamplight.21 During the Summer of 1892 he entered into the bicycling business with none other than Fred Myers. Writing to a northern acquaintance about his new venture Connolly noted optimistically,

You must know that this city is one of the prettiest in the country and has miles of asphalt and hard shell roads. The climate is splendid. There are 400 wheels here and the number is growing constantly. The sport has come to stay and the business is bound to grow for the city is adding to its paved streets.22

Soon thereafter, Connolly was elected Captain of the CLA Cycling Club and aggressively sought to promote the sport on behalf of the Savannah Wheelmen. Less than one year later, and without explanation, he sold his share in the firm of Connolly and Myers to his partner for the grand sum of $1,227.53.23 At the same time, Connolly strengthened his impact on this southern sporting fraternity as he became instrumental in the growth of the Savannah Baseball Club and was granted membership in the Independent Gun Club of the city.24 His civic duty had not gone unnoticed, for in a testimonial written on June 5, 1892, Mayor McDaraugh of Savannah wrote, "This is to certify that Mr. James B. Connolly is well and favorably known to me as the leader in Savannah in cycling and general athletic circles and that his reputation for integrity is unquestioned".25 By the Winter of 1892, Connolly was captaining the Savannah Football Team (by now the city's sole remaining team), and he had embarked upon arranging a full schedule of matches.26 In 1893, at the young age of 24 years, Connolly assumed the role of agent to a local prizefighter by the name of Pat Raedy. Answering a challenge from J. J. McRae which appeared in the Atlanta Constitution, Connolly wrote,

Raedy wishes me to say that he will meet you for $500 aside, and post a forfeit of $200 to bind negotiations, provided your money is posted with some well known man in Savannah or with a bank in Brunswick, Ga. Furthermore, he will allow you $50 for expenses to meet him here in Savannah before a club composed of some of the best men in the city.27

As a recognized sporting and civic leader in Savannah, Connolly was successful in consolidating the city's CLA, YMCA, YMHA and Bicycle Club into one large athletic association with its own sports grounds. Nevertheless, throughout his years in the South, Connolly had maintained contact with many friends within the amateur sporting fraternity of Boston, most specifically Harry Cornish, Secretary of the Boston Athletic Association (BAA), and John Graham, formerly Director of the Charlesbank Gymnasium, and lately Manager and Trainer of the BAA. Before long, he decided to return to New England.28

Sport and Increasing Rationalization in the Global Arena

Altogether dissatisfied with his career path, Connolly sought to regain the lost years of high school through self-tutorial. In October 1895, he sat for the entrance examination to the Lawrence Scientific School and was unconditionally accepted to study the classics at Harvard University. A tryout for the freshman football team was stopped short by a broken collar bone which Connolly later remembered all too well, "...I decided to have a wallop at Harvard football [he wrote], and I turned out with 144 other freshmen candidates. There was a 10 minute scrimmage on the very first day, and after four, or maybe five minutes, a guard of about the build of Dan O'Mahoney crashed me, and did a fine job of crashing."29 It was this incident that prompted Connolly to turn his athletic energies to track and field in which he was far from a novice having already won the amateur hop, step and jump championship of the United States in 1890 as a member of the Trimount Athletic Club of South Boston (a predecessor to the Suffolk Athletic Club).30 Yet Connolly's involvement in sport was to be, it appears, fraught with controversy from the outset. Intent on competing in the revived Olympic Games to be held in Athens from April 6-15, 1896, Connolly submitted a request for a leave of absence to the Chairman of the Harvard University Committee on the Regulation of Athletic Sports. Despite granting Ellery H. Clark, a senior honors student at Harvard, such a request allowing him to join four Princeton University students who had earlier been awarded a similar academic leave, Connolly's request, though apparently endorsed by Dean LeBaron Briggs, was denied by Professor William J. Bingham, Chairman of the Committee, on the basis of his freshman status and mediocre academic standing. Informed that his only course of action would be to resign and make reapplication to the College, Connolly replied "I am not resigning and I'm not making application to re-enter on my return. I am through with this college right now. Good day."31 It was ten more years before he returned to Harvard and then only upon being invited to speak, on the subject of literature, before the Harvard Union. In 1949, he joined the fiftieth reunion of his Harvard class and was presented a crimson letter sweater in track.32

On March 21, 1896, Connolly joined his teammates in Hoboken, New Jersey, and together they sailed to Europe on the S.S. Fulda. Despite his loose affiliation with the "Ivy League," Connolly was clearly the "odd man out." The American team was comprised of Arthur Blake, Thomas E. Burke, Clark, Thomas P. Curtis, William W. Hoyt, John Graham (manager and trainer), Sumner Paine, and John Paine each members of the BAA a stronghold of male Brahmin sentiment, as well as Robert Garrett, Herbert B. Jamison, Francis A. Lane, Scotty McMaster (trainer), and Albert C. Taylor of Professor William Milligan Sloane's Princeton University team. Connolly remained the sole representative of the Suffolk AC of South Boston, proudly wearing its golden stag's head insignia along with a silk American ensign on his singlet. Connolly later explained,

I had been elected to membership in one of the powerful athletic clubs of the country [the Manhattan A.C. of New York] without my knowing anything about it before I went south, but I had never competed for them. I never was strong for those big clubs who were always taking promising athletes away from poor clubs, and keeping them like stables of horses, paying their way and giving them a good time so long as they brought prestige to the big club. I chose to compete for the little Suffolk Athletic Club of my own home town of South Boston, and I was paying my own expenses.33

On opening day in Athens, Connolly won the triple jump (on that day, two hops and a jump!), with a leap of 44'113/4" and, in so doing, became the first victor of the modern Olympic games. He later went on to take second place in the high jump (5'5"), and third place in the long jump (20'01/2"). Returning to defend the triple jump title at the Paris Exposition of 1900 Connolly came in second place. 34 With his name permanently etched in Olympic history, Connolly went on to enjoy a revered status and relative freedom of movement within the frequently aristocratic bastions of American amateur athletics, and the international Olympic movement, at the turn of the century.35

Ten years after his victory in Athens, Connolly provided readers of The Outing Magazine with a lively image of what had represented a modern revival of the Olympic Games. In mottled modesty, Connolly remembered his day, without once mentioning his own name,

It was on directly, the trials and final in the classic Greek jump the triple leap,... and the glorified youth of a dozen nations took their turns, until it simmered down to a Greek, a Frenchman and an American. And the final winning of it by the American led up to an occasion that he has been able since to recollect without greatly straining his faculties. The one hundred and forty thousand throats roared a greeting, and the one hundred and forty thousand pairs of eyes, as nearly as he could count, focused themselves on his exalted person. And then, when his name went up on the board, to the crest of the hills outside the multitude re-echoed it, and to the truck of the lofty staff was hoisted the flag of his country and there remained, while that beloved band of three hundred pieces in the middle of the stadium - and such a band! they should have been admitted to full American citizenship on the spot -began to play the Star Spangled Banner as if it were their own - why, it was a moment to inspire! 36

Patriotism and nationalism appear as common threads throughout Connolly's life. Underscoring his belief in the importance of Flag Day he wrote,

It matters not what country a man chooses to call his own, he must, if he would wish that country well, hold in reverence her institutions. Patriotism will preserve a nation when nothing else survives...

And it is such a tremendous country, this of ours a country into which new millions are ceaselessly pouring; and while these new millions which to them, as yet, mean nothing, but which to us of older citizenship, when we do not forget, mean so much. It is for us to give the lesson.37

Always regarded as a fine American, he nevertheless proclaimed a strong identity and affinity with his Gaelic heritage. Seemingly embraced by "lace curtain" and "rabble" Irish alike, he observed the Black and Tan War in Ireland, first hand, was awarded the Medal of Honor by the American Irish Historical Society, and received the annual medal of the Ireland Society of Boston. His denunciation of the British was both scathing and unceasing. Written in the wake of the controversial London Olympic Games of 1908, Connolly's manuscript entitled "The English as Poor Losers" took direct aim at Anglo-Saxon bigotry and hegemony in sport, as well as their very national character. Providing "tongue in cheek" descriptions of global intrusions into the Englishman's aristocratic traditions of rowing, tennis, yachting, track and field, and even boxing, Connolly went on to systematically criticize the willingness of other nations to tolerate the "sharp practice", decadence, hypocrisy, and excuses of the English sporting establishment. Utilizing the victories of Ten Eyck (rowing), Jay Gould (tennis), Iselin (yachting), Arthur Duffy (track), and other American sportsmen, Connolly concluded that in England "...If your father wasn't a curate, or a barrister, or if he was n't a brewer, or a wholesale dealer in jams, or in some way making his living off the Government, or if he did work with his hands for a living... be sure your entry won't be accepted."38 While Connolly remained convinced that his Irish lineage was, in large part, responsible for his athletic successes, he was also proudly Catholic. "It is in the blood and training of our Catholic boys to be not merely American..." he wrote, adding "...these Catholic youth, patriots and athletes out of all proportion to their numbers, are mostly such because of good Catholic motherhood and a wholesome childhood." Attributing his success further to Catholic confessions and communion, good hygiene and wholesome habits in boyhood, Connolly appeared to stretch his claim too far in suggesting that "...for the supreme champion a Catholic birth and training is almost a pre-requisite."39

By 1906, Connolly's literary career was well-established with the publication of five books and numerous contributions to the Boston Globe, Boston Evening Transcript, New York Sun, and The Youth's Companion, then the most widely circulated boys' magazine in the world. In "The Spirit of the Olympian Games," Connolly followed his verbal applause of the Greek people in 1896 with a call for the establishment of a permanent Olympic site in Athens. Explaining that a decade earlier, "It was difficult to awake our materialists, the men with money to spare, to a sense of the importance of the revival," he added, "We have good men interested in athletics here in America. Some of them are on the American Committee, and, not using athletics for business or social purposes . . ."40 So, in disguised fashion, began Connolly's lifelong criticism of the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU), and its president, James E. Sullivan.41

Sport and Bureaucracy: Capitalist Corruption and Entrepreneurial Exploitation

"How Cronan Went to Athens," tells the story of a young amateur athlete from South Boston named Thomas F. Cronan. The best triple jumper in the nation, Connolly explained,

He belonged to an athletic club [the Shawmut A.C.] whose headquarters were in a little building about the size of four cigar boxes, the same standing on a pier and under the shadow of an elevated trolley bridge, with an inlet of Boston harbor on the other. On summer evenings the members used to swim from off the pier; and they needed to be good swimmers, for it was a swishing current there. In winter they went in mostly for boxing and wrestling; all properly conducted, with a referee, timekeeper, and little clouds of blue smoke floating delightfully under the light of the kerosene lamps.

The driver of a pharmaceutical dray by occupation (for he would not think of deserting the ranks of the amateur), Connolly's story dwelt on the seemingly incessant hardships confronted by Cronan throughout his athletic life, one which was clearly a world apart "From the New York end, where were the official headquarters of the athletic powers." Denying Cronan the opportunity to compete equally for a place on the American team, the Olympic Committee of the AAU had made its selection in executive session. The author explained the outcome thus, "An inspection of the list showed only the names of men from colleges or powerful athletic organizations. Clubs of hardworking lads with their little clubhouses under the eaves of trolley bridges plainly had not been considered."42 In actuality, Connolly had sent a three-page letter to Matthew Halpin, Manager and Trainer of the American team at the 1906 Games in Athens, asserting,

My dear Mr. Halpin:

Messrs. Connolly and Cronan do not care to relinquish the right to have their club named with their entries. It is not hard to understand why. You must be aware that there has been more or less dissatisfaction with the selection of the team...

The names of both these men were sent in to your Committee and both were rejected. One of these defeated Prinstein [one of the athletes selected] the only time they ever met...The other made the best triple leap of all last year in America...

In wishing to have their club named they are simply emphasizing the fact that they were not selected by your Committee....They are going to Greece in any event and they are going to compete. You can do as you please, enter them or not as you see fit. Of course, we all know that the endorsement of the A.A.U. Committee is not at all essential,...

Now as to a matter in which I am interested myself. It was merely as a matter of courtesy and entirely in deference to a suggestion of Mr. Maccabe that I sent on my measurements for the uniform shirt. What you seem to have forgotten is that there is no law bearing on what a man shall wear in competition. And neither is it a question of spirit or patriotism if he refuses to be uniformed pretty much as if he belonged to a fife and drum corps or a class of Y.M.C.A. physical instructors. The flag of our country is the main thing, and we are all going to wear that, and when you suggested that we should have to consult Mr. Sullivan as to what we should have to wear in Athens, you made a beautiful break. A man whose expenses were paid might, possibly, if he is that kind of man, consider that he is tied hand and foot, owned body and soul, by the gentlemen who have the disbursing of the subscriptions of the public. Fortunately we do not come under that head, and hence this feeling of what your Committee may be disposed to call a bumptious independence.

Very truly yours,43

As befitting Connolly's romantic style, which had earlier been developed in his novelette of Spiridon Loues, An Olympic Victor, 44 Cronan took steerage passage to Naples where he "slept in a little shack down a side street" from the American team's hotel "where an orchestra played enlivening airs,. . ." The story's hero "took deck passage down the Adriatic on the same steamer with the officially selected team, who were tucked away in saloon berths,. . ." Cronan's hardship continued in Athens, "the hungry days, the cold nights, the sneers of the manager, the snobbishness, the brutality of the Commissioner." Yet none could dampen his spirits for, encouraged by "the two mighty men from Ireland," Cronan entered and won the triple jump event.45 What read like a piece of fiction was an amalgam of autobiography and fact carefully recounted by Connolly to raise concerns at changes in the bureaucratic structure and discriminatory practices of American amateur athletics at the turn of the century. Two years later Connolly penned a letter to establish a sponsorship fund for one Frank Sheehan who, like Cronan earlier, had not been selected by the AAU to compete at the 1908 Games in London, it read,

On Sunday last there left for England on a cattle steamer, a lad who is probably destined to take rank as South Boston's greatest track athlete. This is Frank Sheehan,... The people who have the say in selecting the American team did not see fit to name him. Our South Boston lad has no representation on the national councils and hence his claim was not pushed...

Athletic authorities who are not playing politics (as well as his friends), believe that young Sheehan is one of the greatest runners living...

He left without money to pay his way on the other side. We hope to raise for him such a sum as will enable him to pay his expenses while in London and a passage back after his race is over. Sheehan knows nothing of this subscription.46

He even blamed the AAU's characteristic American provincialism for overlooking the Gregorian calendar in 1896, resulting in the team's late arrival just one day before the commencement of competition. However Connolly's most severe criticism of the AAU was reserved for an expose entitled "The Capitalization of Amateur Athletics"47 appearing in 1910. In his 12-page treatise, Connolly directly challenged the self-professed guardian of American amateur sport as he systematically took issue with an administrative machine ruled by a long-entrenched, monopolistic and frequently corrupt egotistical oligarchy. He argued quite convincingly that many of the powerbrokers of the AAU were awarded their status by virtue of their pseudo-membership in any number of "fake" or "paper" athletic clubs and who "see in the amateur athletic club as good a means as any other to nurse their local hopes and ambitions;. . ." 48 Moreover, it was his contention that the rise of professionalism must be attributed to these self-serving bureaucrats. He then added,

So the money is passed, and a lad who started out with ideals is led astray, not by an enemy he has been warned against, not by someone in evil guise, but by the priest of his religion . . . He was content once to run or jump his head off for a trophy that might have been worth five, ten, or twenty dollars . . . He was competing because he was in love with the game . . . But now well, a little loose change is a handy thing to have just the same! Somebody gets caught sometime, surely . . . Rare enough; but when the disqualification does come, mark this: It is inevitably the athlete, not the official, who is punished. And the punishment is more than likely to be by way of teaching some obdurate athlete a lesson by the very men who tempted him. 49

Among those specifically targeted for criticism are Joseph B. Maccabe former President of the AAU and member of the "fake" East Boston Athletic Association together with Halpin (who, along with Sullivan the American Commissioner, appear thinly disguised as the officials accused of cheating in "How Cronan Went to Athens"). Halpin was the unnamed American official who was treated with utter disdain by Connolly following the Dorando-Hayes marathon affair of the 1908 Olympics, as he suggested, "He [Halpin] hadn't the guts to go out in the stadium and protest... He stood there moaning until I thought he would cry..."50 Later, in his autobiography, Connolly recalled,

Our little man [Halpin] peered fearfully out at all the red coats in the arena, at King Edward in the royal box, and drew back affrighted. He was that sort, a little man who went servile in the presence of the great... I pushed him into the arena, all but put the toe of my shoe to his stern sheets. He moved out and falteringly entered our protest. The officials reconsidered their decision.51

A former President of the AAU himself, Sullivan was variously described as "an institution," "The Spalding Man," and "The Spalding Agent." Connolly claimed that "Sullivan was the grand jury which indicted as well as the judge and jury which tried and convicted."52 Sullivan was indeed an openly paid employee of A.G. Spalding. In 1892, he was asked to take over the management of the American Sports Publishing Company owned by Spalding, was later appointed Secretary of the national board set up to examine the origins of baseball and, in 1910, led Spalding's failed campaign for the U.S. Senate. Ironically, excerpts from Connolly's critique "The Capitalization of Amateur Athletics," which appeared in Spalding's then hometown newspaper, the San Diego Sun, most assuredly contributed to the premature demise of any political aspirations. At the Paris Olympics in 1900, Sullivan had served as Assistant to the American Commissioner Spalding, while his appointment as Physical Director of the St. Louis Exposition in 1904 guaranteed ongoing endorsement of Spalding sporting goods as the best in the world as well as their ample marketing, for Sullivan was also to enjoy the position of Advertising Manager.53 Such perceived conflict of interest was too much for Connolly who concluded that the Spalding "Athletic Goods Trust," through Sullivan, controlled the legislative process and, more particularly, the Olympic Executive Committee of the AAU,

So paramount indeed is the Spalding influence in the A.A.U. to-day that the name has become a jest among athletes. A man making a new record is greeted with: "Do you wear Spalding shoes? No? Well, you don't get any record." 54

In Connolly's words, "Every young man who registers as an A.A.U. athlete to-day is simply another advertising agent for the [Spalding] Athletic Goods Trust."55 The BAA was, according to Connolly an exception which "always held out for clean athletics." Resisting the call to join those that favoured "a stable of crack athletes at any cost," the Boston organization chose not to promote "The practice of feeding and housing an athlete simply for the advertisement it gave the club."56 Later Connolly lamented the sport's expanding bureaucracy suggesting that "there was only one official with our team of 11 competitors [in 1896]. Last week, I suspect, there were more officials than there were waves on the Atlantic."57

Connolly's recognition of the emerging professionalism in sport had early been made apparent in a four-stanza poem entitled "The Champion Woman Golfer",

Were these days of Ancient Hellas, upon your brow they'd place,

An Olympic laurel chaplet, an honor and a grace;

But ideas of modern glory

Are a journalistic story,

And a thousand silver dollars compounded in a vase.58

Despite his ongoing criticism of sporting commercialism, one is struck by Connolly's own seduction by the entrepreneurial spirit. Earlier documentation suggests a hard-nosed, skilled negotiator who fully recognized and tentatively endorsed the capitalistic potential of sport. Rather ironically, upon his return from Athens in 1896, Connolly accepted the position as professional Editor of the journal Land and Water. The Authority of American Athletic Sports. By this time he was well aware of the financial rewards that athletic success could bring. That same year he joined Robert J. Roberts, Physical Director of the Boston YMCA, in endorsing a medicinal compound claiming, from the site of the first modern Olympics, that, "The Johnson's Anodyne Liniment greatly helped my back which is now entirely well... I am nearly out of Johnson's Anodyne Liniment, as the boys have been calling on me for some."59 Before the 1900 Games in Paris, Connolly traveled with the American team to London where he tried his hand at self-promotion,

I bought a jar of the extract and tried it out. It went all right with me, tasting like beef tea something; so I rounded up our champions and asked them to sign endorsements of the Extract. All but one signed without looking to see how they read... I took my testimonials around to the office of the Food Extract firm... By advice of my advertising counselor I had set the price of one thousand pounds on the endorsements... The Extract Directors held their meeting, admitted the advertising value of the testimonials, and then regretfully returned them. They feared that word would leak out that they had bought them.

Yet this initial rejection of his terms provided just the motivation Connolly needed for, upon the team's arrival in France, he called at the headquarters of a tonic wine company, "So now I got out the testimonials of the athletes, rubbed out the name of the Food Extract, which had been written in pencil for safety, [and] wrote in the name of the Tonic Wine."60 Refused payment once more, the French company did give Connolly two cases of their tonic wine in return for the testimonials, a gift that he used subsequently as partial payment for his lodgings in Paris. After all was said and done, Connolly had the gall to claim that while he and Dick Hunt (a former classmate at Harvard, and team representative in the one mile and marathon), "may have been a couple of tramps at Paris in 1900" that they "surely were real amateurs."61 By 1914, Connolly was endorsing tobacco products once more offering testimony that, "I tried Tuxedo and found a delightful combination of splendid flavor and genuine mildness in this tobacco, that suits me perfectly."62 Earlier still, in 1899, Connolly had accepted the position of Physical Director of the Gloucester Athletic Club in Massachusetts. In this capacity (and still competing under the guise of an amateur), he was paid $25 per week to play for and coach the football team which ended with a record of seven victories and one defeat in its first season. Most important though, Connolly had discovered his "home away from home", a New England fishing port that was to provide both characters and scenic backdrops for his future literary career.

Sport, Technology, and Quantification

Connolly's disillusionment with the modernization of American sport continued with the publication of "Record Breaking." Arguing against the nation's growing fascination with records he wrote,

Comparing new records with old ones does no harm, but to take records over-seriously is something else. The great trouble with records is that they tell only part of the story. They say nothing of the changing rules and other inventions in the athletic world to make record breaking less difficult.63

Using the examples of technological advances in the pole vault (from the long and heavy ash or spruce poles to the lightweight bamboo pole), long jump and track (grass and red clay to cinder surfaces), the intrinsic and extrinsic motivation of amateur and prize events, and John L. Sullivan's renown for never having to knock an opponent down twice Connolly, in true sentimental fashion, defended the athletic exploits of yesteryear as much as he sought to destroy the modern fascination with sports records. "Years ago" he added, "the thing was to win, not set fancy records. And there are a few conveniences that boys have today that my crowd went without."64 Connolly also showed some concern for the increasing emphasis on specialization in sport. Recalling his childhood days in South Boston he wrote proudly, "any of the boys could do several things well, today we would call them all-round athletes."65 Reporting on the 13th Annual All-Round Championship Meet of America, during the Summer of 1897, Connolly argued, "This competition is justly held to be the highest test of an athlete's skill, power and stamina... Any man who can make even a fair total in the all-round programme and finish without collapse... ought easily to win our deep admiration."66

Likewise, the increasing rationalization of sport did not escape Connolly's attention as it became the topic of an article written by him on the eve of the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam. Surprised by the lack of seriousness shown by foreign athletes, Connolly's disillusionment with the character of modern sport was temporarily overshadowed as he marveled in America's "athletic organization; also in [her] elaborate machinery to turn out athletes" adding, "we have more money than any other country to finance athletic programs."67 Connolly's concern with the changing nature of sport is perhaps best revealed through a series of unpublished short stories which, followed the fortunes of a small college football team, and told of its later demise in the professional leagues.Criticizing the emerging excesses in college football during the early years of the twentieth century Connolly accurately, and quite perceptively, identified sportswriters, recruiting practices, increasing spectator interests, economic rewards, academic oversight, increased aggression, role specialization, and psychological provocation as the catalysts to change. Interestingly, Connolly did not allow such criticism to blur the potential benefits of athletic competition as Destin's coach Chet was portrayed as the archetype of his profession, exuding modesty, self-control, and hard work.68

Connolly had much to say about the uses and abuses of alcohol in athletic performance. Drawing from his broad personal experience, he recalled the scene in the dressing room at the first modern Olympics, "...wherein the visiting athletes were privileged to order nourishing delicatessen things and refreshing drinks wines, beer and so on, and all free of charge."69 Later, writing at the time of the repeal of liquor prohibition, Connolly attacked what he perceived to be a national hypocrisy and explained what it was like growing up in a household of teetotalers. He added,

Athletic excellence means physical efficiency... I know intimately hundreds of great athletes...

Of these champions, practically all the Americans were teetotallers in their young days. The European champions were not always so;... But whether teetotallers or not in the beginning, I know of no champion for any great length of time who remained a teetotaller, whereas I did know men who were not teetotallers who lasted quite a while as champions.

The high test of efficiency lies in being able to produce again and again. The most severely tested athletes of my day were the professional runners, jumpers, weight-throwers, and so on, who took part in the Caledonian and Hibernian meets. Foremost was Champion Donald Dinnie he would drink two, four, six or eight bottles of ale after a hard day in the field.70

Repeatedly voicing his support for the old-fashioned virtues of courage, justice and honesty, Connolly vehemently opposed the forces that were moving to change the nature and function of sport in the United States. He staunchly defended the simplicity of sport and the amateur ideal together with the relationship between sport, national pride and national character, concepts which were clearly philosophically opposed at times. He thrived on hero-worship. Whether in his sketches of the lives and exploits of John L. Sullivan or Donald Dinnie, or in creating fictional characters such as Hiker Joy or Dickie, the fundamentally humanistic side of Connolly prevailed throughout his work.71 His ideal was perhaps no better personified than by the Mexican matador, the "supreme" athlete who possessed "strength, agility, speed, nerve, courage, skill all the qualities that a champion athlete in my country needs to have."72 Above all, Connolly genuinely strove to maintain his high personal expectations, faltering occasionally along the way. He was the subject of Theodore Roosevelt's affection when, in 1908, the President of the United States said, "There's a great all-round man Jim Connolly. Mentally and physically vigorous and straight as a whip.I would like my boys to grow up like Jim Connolly."73 While he would later be honored posthumously by the United States Congress it was the following statement, appearing in the text of a letter from Richard Dinneen to Connolly upon the publication of his autobiographical Sea-Borne. Thirty Years Avoyaging, which represented the most fitting testimony,

It takes an exceptional man "to walk with kings nor lose the common touch." Reading your autobiography has convinced me you are that sort of character.74

Connolly's sometimes eloquent, yet always frank, analysis of the changing nature of sport from the last decade of the nineteenth century through the middle of the twentieth century provides a useful, contemporary assessment against which the assertions of others might be measured.

Explaining the Modernization of Sport

In an effort to furnish clear, cogent synthesis with regard to better understanding the process of modernization in American sport, several scholars have demonstrated an apparent ease in categorizing common social denominators.

From Paxson's adaptation of Frederick Jackson Turner's "frontier thesis", to Adelman's explanation for the early development of sport in New York City, and Riess' extended application of Wirth's work, the process of urbanization stands squarely in the forefront of modernization. In Connolly's "world", the spatial, organizational, and human elements of neighborhood clearly contributed fully to the changing complexion of sport. Reaching from the streets of South Boston, to the State Flats, the football fields of the South, and onward to the Olympic stadium in Athens, Connolly found himself in the vanguard of sport's shift from local to international arenas.75 Reflecting a more serious view toward the importance of sport, the growing interest in patriotism and national identity, increased role differ entiation and specialization in sport, ongoing technological development, media and literary coverage, alcohol use, moral and ethical shifts, a fascination with records, and the promise of economic rewards discussed by Connolly, support the notion of increased rationalization. Inextricably entwined with the complexity of modern American sport are the core elements of bureaucratization and commercialization. Adding support for Hardy's claim regarding the central importance of an integrated industry in the process of modernization Connolly, despite his sometimes hypocritical actions, remained an outspoken critic and constant "thorn in the side" of bureaucrats who sought to commercialize traditional, American amateur sport and who, in Connolly's mind, readily exploited the athletes to further their own political and monetary gains.76 Throughout his life James Brendan Connolly, the Olympian and literary romantic, lamented the eternal loss of the once simple, free and healthy institution of American sport practiced by his forbears. A seemingly inevitable metamorphosis which, despite his influence and efforts, he was unable to halt.

See bottom of this page for additional Connolly links.

Notes.

1 The author would like to thank Miss Brenda E. Connolly, together with the staff of the Special Collections of the Miller Library at Colby College, Waterville, Maine, USA, for their invaluable assistance in facilitating this research project.

2 James Connolly, Wrote Sea Tales, 1957, p. 4.

3 Curtis, 1901, p. 4. Among those newspapers and journals for which he wrote were the Boston Globe, the Boston Post, the Boston Transcript, Collier's, Harper's, Sandow's Magazine of Physical Culture, the New York Herald, the New York American, and the Saturday Evening Post. Connolly reported on the Boston Marathon, America's Cup races, and Olympic Games for various journals. He served as editor of the Limelight under the pen name, Greg Binnert, and wrote for Argosy Weekly using the pseudonym, Kevin Johnson.

4 Although not succeeding on either occasion Connolly's platform, which focused on plans for improving the Port of Boston; a stronger navy for defense; legislation to improve the Merchant Marine and to protect dory fisherman from the steam trawler "trusts"; promoting literacy tests for immigrant children in schools; forging protectionist trade tariffs; and supporting legislation for old age and disability pensions, garnered broad, popular support. See, Flynn, n.d., a political campaign prospectus.

5 Marriner, 1949, pp. 7-13; and Jim Connolly, 1918, p. 17. The listing of his citizenship as "Irish", by the United States Olympic Committee, is inaccurate. See, Plant, 1988, p. 68.

6 These include Guttmann, 1978; Betts, 1953, pp. 231-256; Riess, 1989; Paxson, 1917, pp. 143-168; Adelman, 1986; Hardy, 1986, pp. 14-33; and Shergold, 1979, pp. 21-42.

7 Connolly, n.d.(a), pp. 1-4.

8 Enter a Protest for South Boston, 1908; South Boston is Defended, 1908; Connolly, 1908.

9 Connolly, n.d.(a), p. 5. Connolly retained a lifelong affection for John L. Sullivan. Many years after the death of "the Boston Strong Boy," Connolly's previously unpublished typescript entitled Mighty John L., n.d.(g), 17 pp, appeared in a local newspaper under the title, James B. Connolly's Stirring Story to Set John L. Straight Before New Generation, 1933, p. 3.

10 Connolly, n.d. (a), pp. 8-11.

11 Connolly, n.d. (a), p. 13.

12 He early set himself apart from the professional athlete who "in those days could kick up enough in the four summer months to keep him for a year " Connolly, n.d. (a), pp. 14-16.

13 Connolly, n.d. (h).

14 Connolly, 1924, p. 79.

15 Minutes of the Meeting of the Catholic Library Association of Savannah, n.d.; James B. Connolly to Julian R. Leane, February 7, 1892.

16 James B. Connolly to Julian R. Leane, April 9, 1892. Connolly's varied experiences with both small Southern town, and big-time college football provided him with material for a short story entitled Destin Plays Gailer, n.d. (c).

17 Connolly was outspoken on a variety of issues, as one reporter put it, "Jim Connolly is never happy unless he's risking his neck." In, Jim Connolly, 1918, p. 17. Throughout his life he retained a strong dislike of cant and of incompetence in high places. One of his more interesting battles "to clear his name," came in 1908. An apparent failure to pay his membership fees to the Commonwealth Golf Club, resulted in his name being posted in the clubhouse. Revealing an ardent fighter on behalf of principle, lengthy correspondence was interrupted only for his trip to London to report on the Olympics of that year. Finally, upon his return, the matter was settled by each party's attorney. A.M. Jones to James B. Connolly, July 1, 1908; James B. Connolly to H. Thornton, July 3, 1908; James B. Connolly to A.M. Jones, July 3, 1908; A.M. Jones to James B. Connolly, July 6, 1908; F. M. Simpson, to M. J. Connolly, September 12, 1908.

18 James B. Connolly to the Editor of the Atlanta Journal, February 26, 1892.

19 James B. Connolly to the Editor of the Macon News, April 1, 1892.

20 James B. Connolly to J. Brown, April 4, 1892.

21 Connolly, 1944, p. 4.

22 James B. Connolly to Peter Berlo, May 30, 1892.

23 James B. Connolly to Arthur D. Black, September 10, 1893; James B. Connolly to J. H. Polhill, September 10, 1893; James B. Connolly to F. Myers, March 21, 1893; Financial Statement of the Firm of Connolly & Myers, March 15, 1893.

24 James B. Connolly to M. Ellis, June 13, 1892; James B. Connolly to Secretary, Independent Gun Club, August 17, 1892.

25 J. M. McDaraugh to James B. Connolly, June 5, 1892.

26 James B. Connolly to Manager, Mercer College Football Team, December 3, 1892; James B. Connolly to Manager, University of Georgia Football Team, December 3, 1892; James B. Connolly to Manager, Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical College, Auburn Football Team, December 3, 1892; and James B. Connolly to Manager, Furman University Football Team, January 31, 1893.

27 James B. Connolly to J. J. McRae, February 16, 1893. Later, Connolly chose not to act upon a request "to get a pair of featherweights or bantamweights to box 6 rounds and put up a good contest without a knock out... for about $20 each and a rail road fare." See, W. Mead to J. B. Connley [Connolly], North Adams, Massachusetts, December 22, 1902.

28 James B. Connolly to W. H. Lyon, March 10, 1892; James B. Connolly to President of Chatauqua College, Buffalo, NY, March 11, 1892; James B. Connolly to H. Cornish, March 14, 1892; and James B. Connolly to John Graham, March 16, 1892. See also, Connolly, 1897a, pp. 36-39.

29 Connolly, n.d.(f), p.1.

30 Connolly, 1944, pp. 1-4, 9. Connolly provides conflicting evidence here suggesting, in handwritten notes, that the Trimountain (or Tremont) Athletic Club paved the way for the South Bay Athletic Club which was "made up most of working fellows." Connolly, n.d.(b), 6pp.

31 Connolly, 1924, pp. 29-31, 76, 78-80; Connolly, 1944, pp. 9-11. While not graduating from college, Connolly was awarded honorary degrees from Fordham University and Boston College.

32 It should be noted that Connolly had been awarded a letter in track, by the Committee on the Regulation of Athletic Sports, shortly before he dropped out of Harvard in 1896. The "Major H" diploma signed by Committee Chairman William J. Bingham, along with the sweater, is to be found in The James Brendan Connolly Papers, Colby College Library, Maine. During their formative years, the "poor" timing of the Olympic Games effectively excluded American collegians from participating.

33 Connolly, n.d.(f), p. 4. It is interesting to note that in Horton, 1896, pp. 215-229, and Americans Win Olympian Laurels, 1896, p. 243, Connolly is referred to repeatedly by his last name while other team members are addressed by title, first and last name, perhaps reflecting a difference in perceived status. Moreover, a rare photograph of the 1896 American Olympic track and field team, found in The James Brendan Connolly Papers, Colby College, Maine, shows Connolly seated on his own to one side of the team. With Garrett paying the passage of his Princeton teammates, and the BAA providing for its members, Connolly was left to pay his own way in the amount of $700 (drawn from savings put aside for his intended college education), setting the stage for increased representation by Irish-American athletes of the lower socioeconomic strata in future Olympic Games.

34 It would be incorrect to laud him as the first gold medalist insomuch as the victor was awarded a diploma designed by the famous Greek painter Nicolas Gyzis, a silver medal designed by the French sculptor Jules Chaplain (along with the gold-lined, silver bowl presented to him by Prince George of Greece), and a crown of olive branches. All items, with the exception of the olive wreath, are to be found in The James Brendan Connolly Papers, Colby College Library, Maine. Later, at New York in September 1896, Connolly jumped a world record of 49' 1/2" which was to remain unbeaten for thirteen years. See also, Connolly, n.d.(f); and, Connolly, 1936, pp. 24, 28.

35 Among The James Brendan Connolly Papers, Colby College Library, Maine, are to be found volumes of correspondence from former Olympic acquaintances the World over. Connolly remained in favor with the International Olympic fraternity and, in 1954, he was invited to return to Athens for the 60th Anniversary of the Re-establishment of the Olympic Games. J. Ketseas to J. Connolly, April 22, 1954. See also, the emotional letters of Samuel N. Gerson (President of the Philadelphia Chapter of Olympic Athletes), to J. Connolly, November 13, 1946, and November 23, 1946.

36 Connolly, 1906, pp. 102-103; and Schriftgiesser, 1926, p. 3.

37 Connolly, n.d. (d), 4pp.

38 Connolly, 1908b, 14pp. This criticism is perhaps as relevant in debate surrounding contemporary international sports as it was in 1908. In his subsequent rejection of the manuscript, John S. Phillips, Editor of The American Magazine alluded to Connolly's blatantly anti-English sentiment confessing that "It seems that we have a little the same disposition as the English. We just naturally feel, even in victory, that we must go back at the conquered because they don't give us quite full credit for the victory we have won. We are not content with the result; perhaps we have too strong a desire to have them get up and shout, even in their own defeat." John S. Phillips to J. Connolly, September 23, 1908. It should also be noted that Connolly's criticism had begun in an article he wrote, while in London, entitled Charges of General Unfairness, Express (1908). His public questioning of the action of British judges at the Games prompted, not surprisingly, numerous "Letters to the Editor" including the following,

Sir,- A very great part of the long statement with which the American Kipling has favoured us through your columns is merely a rechauffee of the stale old grumblings with which we are so painfully familiar whenever an American meets a Briton in sport. Why on earth we ever ask Americans to compete with us I never can understand...

Badminton Club H. F. K.

39 Connolly, 1923, pp. 312-321. In this chapter, the author underscores his claims with sketches of prominent, mostly Irish-Catholic, American sporting champions.

40 Connolly, 1906, p.104.

41 Connolly's earliest documented communication with Sullivan comes in a letter addressed to Mr. James E. Sullivan [then Secretary of the Amateur Athletic Union], from James B. Connolly, February 1, 1893, In the letter, Connolly requests information on the schedule of the World Championships planned for Chicago during September 1893. Showing neither animosity nor antagonism of any kind at this time, Connolly indicates that he was first introduced to Sullivan on April 12, 1890 in Boston by Mr. Harry Cornish. See also, Korsgaard, 1952.

42 Connolly, 1910a, pp. 466-467.

43 J. B. Connolly to Matthew P. Halpin, March 28, 1906.

44 Connolly, 1908a. An Olympic Victor: A Story of the Modern Games, first appeared as a serial in Scribner's Magazine. The James Brendan Connolly Papers, Colby College Library, Maine, include a manuscript of a stage version of An Olympic Victor which culminates in a finale aptly titled "a ballet of sports", and featuring theatrical runners, jumpers, discus throwers, hurdlers, oarsmen, as well as "a triumphant march of victorious athletes".

45 Connolly, 1910a, pp. 468-475.

46 Open letter to prospective sponsors from J. B. Connolly, South Boston, June 30, 1908.

47 Connolly, 1910b, pp. 443-454. Encouragement for writing his indictment of the AAU had come from John C. Phillips, Editor of The American Magazine some two years earlier. Responding to a letter written by Connolly upon his return from the 1908 Olympics, Phillips replied, "I am very much interested in the suggestion made in the postscript of your letter about the Amateur Athletic Union... It seems to me that amateur athletics can only be kept up to the proper standards by those taking part in games and contests who are real amateurs and who intend to remain so... If you do this article, I should be very glad to have you let me see it." John S. Phillips to James B. Connolly, New York, September 23, 1908. Shortly thereafter, Connolly's manuscript arrived at the offices of The American Magazine in New York, prompting a rejection from Phillips who added, "I can see that there is real stuff in the subject,... You are evidently mad. I should rather have the anger a little less obvious and more facts... I would not call it exactly a safe article on the subject." John S. Phillips to James B. Connolly, New York, October 26, 1908.

Apparently The American Magazine's concern with libel had some grounding, for a full two years after the appearance of Connolly's article, Messrs. Sullivan and Halpin brought legal action against Connolly and The Metropolitan Magazine. The Metropolitan Magazine to James B. Connolly, New York, June 27, 1912.

48 Connolly, 1910b, p. 443.

49 Connolly, 1910b, p. 446.

50 Connolly, 1932b, p. 30.

51 Connolly, 1944, p. 149.

52 Connolly, 1910b, p. 451. It seems entirely likely that Connolly's animosity was fueled by an inexplicable newspaper editorial provided by James E. Sullivan (then Secretary-Treasurer of the AAU), which elaborated on accusations of cowardice and self-interest levelled at Connolly on the occasion of an accident at sea, in which he was involved, between the SS Republic and SS Florida. ConnollyThat's All, 1909, p. 4. This led Connolly to file a libel suit against the New York Times, World, and Sun the outcome of which is unclear.

53 Levine, 1985, pp. 82, 113-114, 119-120, 134-142.

54 Connolly, 1910b, p. 450.

55 Connolly, 1910b, p. 454.

56 Connolly, 1897a, pp. 36-38.

57 McKenney, 1948, p. 4. Connolly's most extensive critique of the bureaucratic ownership and control of individual athletes appeared in, Connolly, 1928, pp. 8-10, 47.

58 Connolly, 1897b.

59 Quoted in a letter from James B. Connolly to James S. Murphy, March 29, 1896 appearing in an advertisement for Johnson's Anodyne Liniment. James Shield Murphy, Souvenir of The Olympic Games at Ancient Athens April 5th to 15th, 1896. Boston: I. S. Johnson & Co., 1896, 16pp. The same advertisement later appeared in The Golfer 7:4 (August 1898).

60 Connolly, 1928, pp. 8-10, 47. Returning to Boston in "steerage with 2,100 emigrants aboard," Connolly recalled "The first thing I did after I got home was to write two stories for a boys' magazine. I got $50 a piece for them... Those stories were the first fiction things I ever wrote".

61 Connolly, 1928, p. 10.

62 W. R. Ellis [Connolly's agent] to James B. Connolly, March 6, 1914, regarding a contract with Frank Presbrey Co., advertising agents for American Tobacco Co. By 1920, Connolly had secured the services of Thomas Brady, an agent with a prominent New York lecture, entertainment, and musical bureau.

63 Connolly, 1937, pp. 17, 68-69.

64 Sullivan, 1956, p. 5.

65 Connolly, n.d.(a), p. 3.

66 Connolly, 1897c, pp. 34-35. Later, Connolly's vivid description of the failed attempts of a "new breed" of field goal specialist in college football was followed by the glorious attributes of his fictional hero who could "punt, drop kick, pass, run and play a swell defensive game," In, Connolly, n.d. (c), p.17.

67 Connolly, 1928, pp. 8, 41.

68 Connolly, n.d.(c) p. 22, and Connolly, n.d.(i), pp. 22.

69 Connolly, 1932a.

70 Connolly, 1933, pp. 3-4. The alcohol-athletic debate is further developed, though in rather anecdotal and romantic fashion in, Connolly, 1939, pp. 27, 74-75.

71 Treacy, 1943, pp. 99-103. In, Connolly, 1907, p. 246, the author tells the story of a high school track race. Dickie, the young "rabbit", finds the strength to come from behind, and rise from his place as underdog (when Sullivan his teammate and the school champion fades), so bringing victory and honor to his school.

72 Connolly, n.d.(e), 13pp., is a short story that represents a partial defense of Mexican bullfighting.

73 President's Grip Makes Discus Thrower Wince, 1908, p. 1; Roosevelt's Ideal of an All-Round Man is J. B. Connolly... Hopes Teddy, Jr., Will Be Like Him, 1908, p. 1. These articles were an outcome of President Roosevelt's interview, at The White House, with Martin J. Sheridan, champion all-round athlete and member of the Irish American Athletic Club of New York.

74 James Brendan Connolly, 1960, p. 6375; Richard Dinneen to J. B. Connolly, January 23, 1945.

75 Paxson, 1917; Adelman, 1986; Riess, 1989; and, Wirth, 1938, pp. 1-24. See also, Hardy, 1981, pp. 183-219.

76 Rationalization and bureaucratization represent two of the seven distinct characteristics of modern sport identified by Guttmann, 1978; and, Hardy, 1986. See also, Betts, 1953 and Shergold, 1979. Not surprisingly, these elements reflect the characteristic change from traditional to modern societies and institutions presented in, Brown, 1976.

References

Adelman, Melvin L. A Sporting Time. New York City and the Rise of Modern Athletics, 1820-70 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986).

Americans Win Olympian Laurels, Scientific American, 74 (April 18, 1896), p. 243.

A.M. Jones [Secretary-Treasurer of the Commonwealth Golf Club] to James B. Connolly, July 1, 1908. Letter, The James Brendan Connolly Papers, Colby College Library, Maine.

A.M. Jones [Secretary- Treasurer of the Commonwealth Golf Club] to James B. Connolly, July 6, 1908. Letter, The James Brendan Connolly Papers, Colby College Library, Maine.

Betts, John Rickards, The Technological Revolution and the Rise of Sport, 1850-1900, Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 40 (September 1953), pp. 231-256.

Brown, Richard D., Modernization: The Transformation of American Life, 1600-1865 (New York: Hill and Wang, 1976).

Connolly, James B., The Boston Athletic Association, Land and Water, 1:2 (August 1897a), pp. 36-39.

Connolly, James B., The Champion Woman Golfer, The Golfer, V:V (September 1897b).

Connolly, James B., What Constitutes an All-Round Champion, Land and Water, 1:2 (August 1897c), pp. 34-35.

Connolly, James B., The Spirit of the Olympian Games, The Outing Magazine, (April 1906), pp. 102-103.

Connolly, James B., The `Second String', The Youth's Companion, (May 17, 1907), p. 246.

Connolly, James B., An Olympic Victor: A Story of the Modern Games, (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1908a).

Connolly, James B., The English as Poor Losers. Unpublished manuscript, (1908b), 14pp. The James Brendan Connolly Papers, Colby College Library, Maine.

Connolly, James B., How Cronan Went to Athens, Everybody's Magazine, 22 (April 1910a), pp. 466-467.

Connolly, James B., The Capitalization of Amateur Athletics, Metropolitan Magazine, (July 1910b), pp. 443-454.

Connolly, James B., Catholic Leadership in American Sport, in: McGuire, C. E. (ed.), Catholic Builders of the Nation (Boston: Continental Press Inc., 1923), pp. 312-321.

Connolly, James B., The First Olympic Victory, The Elks Magazine, (July 1924), p. 79.

Connolly, James B., The Free Olympic Days, Columbia, 2 (September 1928), pp. 8-10, 47.

Connolly, James B., I Was First Olympic Victor in 1500 Years, Boston Sunday Post, (July 31, 1932a).

Connolly, James B., Some Olympic Thrills and Personalities, Columbia. XI:12 (July 1932b), p. 30.

Connolly, James B., Alcohol and Efficiency, Limelight, I:5 (December 27, 1933), pp. 3-4.

Connolly, James B., Fifteen Hundred Years Later, Collier's, 98 (August 1, 1936), pp. 24, 28.

Connolly, James Brendan, Record Breaking, Colliers, 100 (1937), pp. 17, 68-69.

Connolly, James Brendan, Oh, How They Ran! Collier's, 104 (September 16, 1939), pp. 27, 74-75.

Connolly, James B., Sea-Borne: Thirty Years Avoyaging (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Doran and Company, Inc., 1944).

Connolly, James B., [An Ex-Champion Amateur Athlete], The Amateur Athletic Spirit, Unpublished manuscript, n.d.(a), pp. 1-4. The James Brendan Connolly Papers, Colby College Library, Maine.

Connolly, James B., The Athletic Game, Unpublished manuscript, n.d.(b), 6pp. The James Brendan Connolly Papers, Colby College Library, Maine.

Connolly, James B., Destin Plays Gailer, Unpublished typescript, n.d. (c), 17pp. The James Brendan Connolly Papers, Colby College Library, Maine.

Connolly, James B. Flag Day and What it Means, n.p., n.d. (d), 4pp. The James Brendan Connolly Papers, Colby College Library, Maine.

Connolly, James B., The Last Bull Fight, Unpublished typescript, n.d.(e), 13pp. The James Brendan Connolly Papers, Colby College Library, Maine.

International Olympic Committee information and pictures of Connolly and the 1896 American Olympic Team.

James Connolly (athlete), From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

The Unexpected Olympians. A Harvard Magazine article on one of that school's more famous non-graduates, J. B. Connolly, that includes an interesting quote: regarding his withdrawal from Harvard, "That's how Connolly remembered the incident 48 years later. It makes a good story, but is somewhat at odds with the truth, which Connolly made a lifelong habit of bending."

The Irish American Trail. James Brendan Connolly Statue in South Boston commemorates his Olympics victory in 1896.

The First Olympic Champion, an article from the Journal of Olympic History, a excerpt of Connolly's own writings on the 1896 Olympics.

James Connolly, Fact Index, a brief biography.