To reiterate, when market conditions were conducive for gold exports to Europe, bankers would secure bars from the Assay Office. Bars were packed in kegs (also referred to as "casks" or "barrels"), six bars to a keg, each keg worth approximately $48,000 and weighed approximately 165 pounds.1 Bars would be purchased and exported by weight. Only if the Assay Office were to exhaust its supply of gold bars, and market conditions remained favorable for the continued export of gold to Europe, would bankers purchase gold coin from the Sub-Treasury. Sub Treasury, interior, circa 1920

3. Security Measures. Each step of the engagement transaction, from initial placement through shipment and ultimate receipt, would have its own security procedures that would restrict factual information to those individuals who were on a need-to-know and when-to-know basis. Shipment details, such as the scheduled shipping date and the name of the transporting vessel, were occasionally reported in the newspapers along with the engagement information, and were regularly reported in the Journal of Commerce as part of that paper's U. S. Customs House export reports. However, it is well known among researchers today, and was known among moderately inquisitive individuals at the time, that this shipping information was often deliberately deceptive. For example, engagements were reported routinely as being shipped "to-day" or "on to-morrow's steamer." With information such as this, it would be virtually impossible to plan a robbery on a shipment that had already left or was about to leave in only one day, when, in actuality, the shipment would or could leave much later. These deceptions were used as a systematic means to thwart any possible robbery attempt. This can be seen if we put the era in context. It was an era in which individuals in decision making capacities had lived through a time of train and bank robberies. The wireless telegraph had been only recently invented and its worth at sea had not yet been proven. In addition, when performing properly, its maximum range was limited to within only 300 miles. However, the trans-Atlantic telegraph cable was in place and commonly used as a means of communication. This situation left gold shipments, particularly on vessels without wireless, vulnerable to in-transit theft between vault and pier, pier theft, cargo theft, crew mutiny, mid-ocean piracy, and premeditated theft at the receiving port if the reported shipping details were accurate. If, however, the reported shipping details were questionable, and known to be questionable, the security of gold transactions would be greatly improved. Even in today's sophisticated transportation systems that inherently utilize high-technology surveillance, communication and tracking capabilities, banks do not "advertise" their armored car schedules. Gold, currency, negotiable securities, diamonds, artworks and other extreme valuables are shipped daily via airports worldwide, but you cannot find a schedule. And if such a schedule were available, who would be so foolish to publish for the world's consumption a truthful account, and who would be so foolish to believe it? Receiving, Loading, Stowage and Delivery Specie (See Bullion) Bullion PRECIOUS CARGO

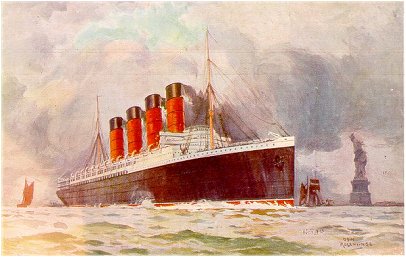

Neither was the fact of an actual gold shipment aboard a particular vessel common knowledge to its passengers or crew for the same security reasons. Of course, the Captain's responsibility was for the operation of the vessel and the safe passage of its passengers and cargos. The Purser was responsible for the business affairs of the vessel and, generally, the First Officer was responsible for security cargos. These officers would be aware of their ship's gold cargos. Gold shipments were further concealed from those not on a need-to-know basis, and to thwart any mid-ocean piracy attempt, by being manifested separately; routinely, gold would not be listed on the main cargo manifest, but would be accompanied by its own, separate manifest, which allowed, essentially, "bearer" presentation.9 Cunard Liner R.M.S. Lusitania Reported shipping details for the period are rare, but, when reported, they provide some detail on procedure. BIGGEST GOLD CARGO Over $12,000,000, Brought on WAS PACKED IN 334 BOXES Crowd Watches It Hustled Out of the

N. Y. Times, November 9, 07, 2:3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

FOOTNOTES1Based on the $9,805/500 ounce gold value, a $48,000 keg would weigh 2448 ounces troy. 2RECOLLECTIONS OF A NEWSPAPER MAN - A Record of Life and Events in California by Frank A. Leach, published in 1917 by Samuel Levinson of San Francisco, Chapter XVI, available on-line at: http://www.coinfacts.com/historical_notes/frank_leach.htm. Leach was Superintendent of the United States Mint at San Francisco from 1897 to 1907 and Director of the Mint at Washington from 1907 to 1909. Leach was intimately involved in the development of the new coin designs promoted by President Teddy Roosevelt -- this story gives fascinating "insider" details from the man who oversaw several of the projects, including the movement of millions of dollars in gold coin, in mostly $5 million shipments, from the San Francisco Mint to the Denver Mint; the shipments that Leach describes began August 15, 1908 and ended December 19, 1908. 3Based on the $9,805/500 ounce gold value, a $5,000 bag would weigh 263 ounces troy. 4With three - five 500 troy ounce bags to a coin box, each box could hold between 125 and 171 pounds of gold coin. Kegs held, apparently, the same weight-range for bars, and therefore a weight of 18 lbs/bag x 8 bags = 144 pounds and a face value of $40,000 per coin box is calculated. This value per box is confirmed by the description of the LUSITANIA's gold cargo in the N. Y. Times article of November 9, 1907 - where 334 boxes equal $12,361,150; this computes to $37,000 per box. With the LUSITANIA's 14 consignees and differing, non-uniform amounts for each consignee, several of the boxes would be partially full and would reduce the average contained per box. 5See N. Y. Times, November 9, 07, 2:3, infra. 6Coin box and bag photos taken at Federal Hall (the former US Sub Treasury), New York, of their coin-vault display, December, 2004. 7 Stowage, The Properties and Stowage of Cargoes, R. E. Thomas and O. O. Thomas, Brown, Son & Ferguson, Ltd., Glasgow, 1928, Page 109-110. 8Practical Cargo Stowage for Ships' Officers, H. H. Brider and O. M. Watts, Imray, Laurie, Norie & Wilson, Ltd., London, 1930, Pg. 150 - 151. See also: Notes on the Stowage of Ships, Charles H. Hillcoat, Colonial Publishing Co., New York, 1919, Pg. 110-111. 9Determined empirically from a study of inbound and outward manifests appearing in the Journal of Commerce. Although gold imports and exports would be listed by ship in the U. S. Customs weekly report, gold shipments cannot be located within corresponding printed manifests. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| . . | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||