Navy Payroll and Operational Funds.

The United States Government has recently filed a claim in our salvage action based, at least, on the following analysis. Their claim for the loss of "gold coin or other specie and other legal tender being transported on the R.M.S. Republic ..." can be found at our Legal Section.

The United States Government has recently filed a claim in our salvage action based, at least, on the following analysis. Their claim for the loss of "gold coin or other specie and other legal tender being transported on the R.M.S. Republic ..." can be found at our Legal Section.

There is evidence that suggests both a need for gold coin by the Great White Battleship Fleet and the opportunity for shipment and ensuing loss aboard the REPUBLIC. Although the amount of possible Navy monies does not approach the legendary $3,000,000 (1909 value, worth potentially in excess of $1 billion in today's market) American Gold Eagle shipment (see: The Three Million Dollar Transaction, et seq. for a description of that cargo.), it does compare favorably to the amount of gold reportedly taken aboard the REPUBLIC as identified by REPUBLIC passenger James Connolly; evidence suggests that funds for Navy operating expenses, including payroll, of between $250,000 and $350,000 in coin monies, worth potentially fifty to seventy million dollars in today's market, may be aboard the REPUBLIC. |

31. As soon as it had been definitely decided to present all of the provisions of both supply ships to the Italian disaster sufferers, the department cabled to the commander in chief asking what quantities of each item of provisions would need to be shipped via the steamship Carmania, which would arrive at Gibraltar about January 25.1, 2 The commander in chief at first replied that whatever supplies were needed could be purchased in Europe. A further inquiry, however, being received from the department along the same lines as the former query, the commander in chief stated how much of each article were needed to carry the fleet into Hampton Roads. [Emphasis supplied]

32. A few days later cable advice was received from the department to the effect that the Carmania was not available2 and inquiring whether it would be practicable to receive the same supply of fresh provisions from the steamship Republic, scheduled to arrive at Gibraltar just before the fleet itinerary called for departure for Hampton Roads. The reply of the commander in chief was to the effect that the cargo would be immediately discharged from the Republic and distributed among the various vessels of the fleet.

33. On the afternoon of January 24, the flagship being then in the port of Villefranche, France, the commander in chief received a cablegram from the department stating that the steamship Republic had that day sunk[?]3 off Nantucket, with all the fresh provisions for the Atlantic Fleet on board.

34. The situation brought about by this information was very grave indeed. ...4

839. (1) Each member of the crew, except such as may be in confinement as punishment, serving sentence, or awaiting trail, shall be allowed to draw monthly such money as he may have due him on the payrolls...

(4) Monthly money shall be paid on the 25th of each month, unless that day falls on a Sunday or a legal holiday, in which case it should be paid on the preceeding or following weekday. If it be impracticable, when at sea, to pay on that date, it should be paid as soon after as conditions warrant; but nothing herein contained shall be construed as preventing the captain from granting, for reasons satisfactory to himself, special requisition for money at other times. ...

Regulations for the Government of the Navy

of the U. S., U. S. Navy, 1909, Page 195.

Funds for operational expenses - the purchase of coal, supplemental provisions, payroll, etc. - were paid in gold by funds maintained within the Fleet Paymaster's office. Funds in gold coin were drawn on Navy accounts maintained at both the New York and San Francisco Sub-Treasuries. Overseas disbursements were made in the indigenous gold currency which was generally obtained locally by way of bills of exchange.

The REPUBLIC was carrying fresh provisions, which were to replace those provisions which were given by the Fleet as earthquake relief, sufficient to complete the cruise and "carry the fleet into Hampton Roads." The provisions were originally scheduled to be shipped by the Cunard Liner CARMANIA, which was to arrive at Gibraltar "about" January 25th (a payday!). The CARMANIA, however, was to the effect...was not available2 and, as a result, the supplies were placed aboard the REPUBLIC.

The question, then, is - Did the Atlantic Fleet have sufficient cash to meet both its January 25th payroll and operational expenses which were to be incurred through and upon departure from Gibraltar to arrival in Hampton Roads, Virginia? Four (4) related, although independent, views of the operational data support both the need for U. S. gold coin by the Atlantic Fleet and the possible loss of this gold aboard the REPUBLIC.

I. A basic balance sheet for gold funds maintained by the Atlantic Battleship Fleet can be made from available data contained within the report "Operations of Pay Department of the Atlantic Fleet on Cruise Around the World," previously cited.

| Fleet Balance Sheet | ||||

| Date | Item | Debit | Credit | Balance |

| 09/22/08 | At sea - Gold in Fleet ($243,133 + £47,930 =) | $476,384.365 | ||

| 09/29/08 | At sea - Gold in Fleet ($230,288 + £37,132 =) | $410,990.886 | ||

| [Average specified expenditures per month for the entire fleet (as reported7) were $371,000, which computes to a daily expenditure of $12,367. The difference between the two reported balances, above, computes to a weekly expenditure of $65,393.48 or $9,341.93 per day. With the Fleet at sea, having departed Albany, Australia on September 18th and arrival at Manila, P.I. on October 2nd, the primary expense would have been the September 25th payroll, with a now computed Fleet payroll of approximately $65,000 per month. Because the primary expense incurred for this period was payroll, the average expenditure for this period would be less because it does not include most operational expenses.] | ||||

| 10/04/08 | Deposit - Manila | $350,000 | $760,9918 | |

| 11/05/08 | Expenditures 9/23 - 11/05 | $531,7819 | $229,210 | |

| 11/06/08 | Deposit - Manila | $400,000 | $629,21010 | |

| 12/13/08 | Expenditures 11/06 - 12/13 | $519,414 | $109,796 | |

| 12/14/08 | Deposit - Colombo, Ceylon (£75,000 =) | $364,988 | $474,78411 | |

| 01/08/09 | Expenditures 12/14 - 01/08 | $309,175 | $165,600 | |

| 01/09/09 | Deposit - Port Said, Egypt (£58,500 =) | $284,690 | $450,29012 | |

| 01/25/09 | Expenditures 01/09 - 01/25 | $197,872 | $252,418 | |

| 02/22/09 | Expenditures 01/26 - 02/22 | $346,276 | (-$93,858)13 | |

Because amounts for "various auxiliaries" and a "usual fleet reserve fund of $42,672.82"14 were maintained, on-hand cash within the Fleet is not shown to fall below $100,000. Therefore, an analysis of Atlantic Fleet operational data suggests that the Fleet would have required additional funds to avoid a negative balance; in order to maintain at least a $100,000 surplus, the Fleet would have required in excess of $200,000. This amount is in compliance with the amount reported by Mr. Connolly as that which was taken aboard the REPUBLIC.

Certainly, too, the Fleet had also incurred additional and unanticipated cash expenses as a result of its spontaneous participation in the Italian earthquake relief effort; the earthquake took place on December 28, 1908. These additional expenditures are not reflected in the above analysis. See also: US Government Relief Funds.

II. Cash disbursements were made in the indigenous currency of each port of call, with British Gold Sovereigns as the preferred currency for Mediterranean ports. The Fleet had, in fact, deliberately exhausted its supply of U. S. gold coinage prior to arrival in Mediterranean ports.

...when making payments in Japan the supply of United States gold is to be exhausted, so that as far as practicable the entire amount remaining for use after final departure from Manila will be in British gold.15

...all arrangements have been made for supplying the fleet with funds until final departure from the Mediterranean for home...16 [Special emphasis.]

From the date of departure from Manila until the fleet leaves the Mediterranean for home, payments in United States money will be discontinued; and all expenditures will be made in British gold...17

It is assumed that, with the Fleet's next port of call at Hampton Roads, Virginia, and having exhausted all U. S. gold prior to arrival at Mediterranean ports, there would have been a need, or at least a preference, to disburse the January 25th payroll at Gibraltar (and all subsequent disbursements) in U. S. gold.

The Fleet arrived at Gibraltar, January 31 - February 1, 1909.18 It is interesting to note that no shore liberty was given to the US Fleet's sailors at Gibraltar19, perhaps to conserve cash funds. After the loss of the Republic's cargoes, Fleet Paymaster McGowan purchased $50,000 of supplies at Marseilles to replace those lost aboard the Republic - so that the Fleet would have sufficient provisions to complete its journey to Hampton Roads. These supplies were delivered to the various ships; the respective paymasters paid for the supplies with both French and British gold specie.20

III. Funds were, whenever possible, requisitioned in advance. As indicated by the Fleet's receipt of funds (above I), funds were received by the Fleet generally within the first ten days of each month. The subsequent disbursements to the Fleet also support both the average rate of expense, previously used and identified in this report, and the monthly timing for receipt of funds.

That $500,000 be placed to the credit of the fleet paymaster at Boston, July 3, 1909, so that he can obtain that amount of cash July 5, 1909, for distribution among the vessels of the fleet for July disbursements. ...That an equal amount be similarly placed at Norfolk, August 9, 1909, for August disbursements. ...21

With a payroll day occurring on the 25th, efficiencies could be achieved by the receipt of operating and payroll funds approximately mid-way between paydays.

Based on this monthly pattern, funds should have been available to the Fleet on or about February 9th, except for the fact that the Fleet would be at sea, having departed from Gibraltar on February 6th.22 Therefore, it can be anticipated that funds would have been requisitioned for delivery to the Fleet at Gibraltar, prior to its departure for Hampton Roads, Virginia.

The Republic was scheduled to arrive at Gibraltar February 2nd, 1909.23

IV. If the loss of payroll and operating funds had occurred, and with insufficient time to replace those funds prior to the Fleet's departure from Gibraltar, it would be expected that the Fleet would receive more funds than that which would normally be required upon the Fleet's return at Hampton Roads, Virginia.

U.S.S. Connecticut (Flagship),

Cavite, Philippine Islands, Nov. 18, 1908

Sir: The fleet paymaster will furnish funds after arrival in the United States in the same manner as at Manila, namely, by depository checks in fulfillment of pay officers' requisitions on S. & A. Form No. 15. ...

Requisitions for sufficient funds to make all expenditures from February 22 to and including March 31, 1909, should be in the hands of the commander in chief not later than December 15, 1908.

By direction of the commander in chief:

A. W. Grant

Commander, U.S. Navy, Chief of Staff.24

Estimated that $1,000,000 would be needed by the fleet on its arrival at Hampton Roads...25

. . . After coaling at Tetuan Bay [on the north coast of Morocco], the Yankton will proceed independently [to the US] by a more southerly route than the rest of the fleet, going by way of the Azores and Bermuda, in order to avoid bad weather. She is due at Hampton Roads a day ahead of the fleet.

NY Times, Jan. 27, 09, 4:4

The Yankton, as was her practice, preceded the Fleet in its journey.26 However, it is worthy to note that Sperry issued his order for the Yankton to return to Hampton Roads, and to arrive there one day ahead of the fleet, on January 24, 1909 - the very day that he had learned of the Republic's loss. See: Historical Documents. After coaling, the Yankton departed Gibraltar February 1, 1909 for her homeward-bound Atlantic crossing. She stopped briefly at Funchal, Madeira on February 3rd, and departed there February 4th. She arrived at Hampton Roads on February 17, 1909. 27

As she was passing between Capes Henry and Charles, the Yankton was ordered via wireless, immediately after she had completed coaling at Hampton Roads, to proceed to Washington, DC.28 Upon her arrival at the Washington Naval Yard on February 19, her Captain, Lieutenant Commander C. B. McVay, reported to the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation and the Secretary of the Navy. At the Navy Yard, the Yankton received three wooden boxes from the yard, . . . [On February 20, 1909, 8 A.M. to Meridian, Yankton received ] 18 bags confidential mail & 20 secret codes for atlantic fleet. Received from U.S. Treasury $800,000 which was placed under lock & key and sentry's charge29 for transport to the Fleet.

When she returned to Hampton Roads, arriving there on February 22, 1909:

Meridan to 4 P.M. ... At 2:15 the Executive Officer with six men reported on board flagship. At 2:30 the Commanding Officer left the ship and called officially on the President of the United States and the C in C [Commander in Chief of the Fleet]. At 2:40 the President went on board the flagship and afterwards he visited each flag ship in turn. All ships observed the usual ceremonies.

February 23, 1909: 8 A.M. to Meridian . . . The Commanding officer delivered the following: 4 bags Confidential mail and 19 secret codes to the Commander in Chief; 3 bags Confidential Mail to the 2nd division Commander, 4 bags Confidential Mail to the 3rd division Commander, 2 bags Confidential Mail to the 4th division Commander, 1 bag Confidential mail to the Maine. The Paymaster delivered $610,000 to the paymasters of the fleet. . . .

Meridian to 4 P.M. . . . The paymaster delivered $110,000 to the paymasters of the fleet and $70,000 to the Fleet Paymaster.30

The funds (in the amount of $800,000) [parenthetical comment in original] requisitioned by me were sent to Hampton Roads by the Yankton, and distribution was made direct to the several pay officers February 23.31

$800,000 GOLD FOR FLEET

The Yankton Takes Money to Pay the

Officers and Men.

WASHINGTON, Feb. 20. - Carrying $800,000 in gold pieces fresh from the Government Mint to pay the officers and men of the Atlantic fleet, the gunboat Yankton, which yesterday completed its cruise around the world, left to-day for Norfolk to rejoin the fleet. The Yankton also took a supply of the new signal code. ...

New York Times, February 21, 09, 2:7

Although the Yankton, like other ships of the Fleet, carried her own monthly operational funds, we have not found any other instance where the Yankton carried the Fleet's funds. Her early arrival to the US coupled with the orders she received upon arrival, her Commander's meetings with the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation, the Secretary of the Navy, and the President, and her mission to acquire funds from the US Treasury, Washington, DC, and deliver those funds to the Fleet - was, to say the least, a sequence of out-of-the-ordinary events. It was routine for Navy cash funds for the Atlantic Fleet to be disbursed from the New York Sub Treasury, not the US Treasury at Washington, DC; the San Francisco Sub Treasury handled funds for the Pacific Fleet.

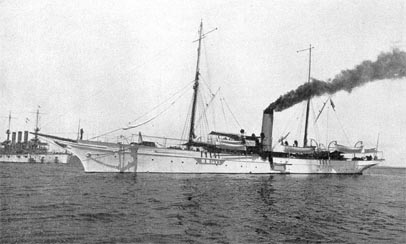

Yacht Yankton32

The amount of funds distributed to the Fleet upon its arrival at Hampton Roads, too, is unusual. $800,000 for the period February 22 to and including March 31 (37 days), significantly exceeds the amount which would normally be required for payroll and operational expenses for the same period. Based on the average rate of expense previously identified, $12,367/day, $457,579 should have been the amount required for this period. An unidentified excess of close to $350,000 was distributed to the Fleet upon its arrival at Hampton Roads.20

The manner in which the Fleet received its funds at Hampton Roads was unusual. The Fleet's receipt of funds on February 20th, 1909, was inconsistent with its normal monthly funding pattern. And, the amount received was inconsistent with its monthly funds expenditure. A shipment of approximately $265,000 aboard the Republic, and its proposed delivery to the Fleet on February 2, 1909, would be consistent not only in the method that the Navy often used in the shipment of funds - shipping funds by commercial vessel, but would also be consistent with the Fleet's normal source of funds, the New York Sub Treasury, as well as the Fleet's monthly funding pattern and funding needs.

Since the Republic did carry at least "provisions" for the Atlantic Fleet, why wouldn't she also carry any required funds?

The Russian gold, if it exists, would have been the primary reason to keep from public view the loss of Navy funds. A public inquiry would have been circumvented, which may have leaked information concerning the Russian cargo. A public investigation was particularly inopportune for cargoes which were then beyond recovery and whose loss, in the case of the Russian gold, if disclosed, would have lessened investor resolve in maintaining the Russian autocracy.

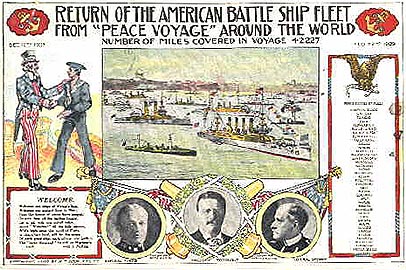

Teddy Roosevelt, too, had sent the Fleet around the world under a good deal of criticism and political risk. At the Fleet's return to Hampton Roads on February 22, 1909, Roosevelt

was in a joyous mood. "Do you remember," he askt [sic] a friend, "the prophecies of disaster? Well, here the ships are, returning after fourteen months without a scratch." Visiting the four flagships, he made a brief address to the officers and men on each of them. Speaking to Rear Admiral Sperry and his men on the "Connecticut," he said:![]() "You have falsified every prediction of the prophets of failure. In all your long cruise not an accident worthy of mention has happened to a single battleship, nor yet to the cruisers or torpedo boats. You left this coast in a high state of battle efficiency and you return with your efficiency increased - better prepared than when you left, not only in personnel but even in material.

"You have falsified every prediction of the prophets of failure. In all your long cruise not an accident worthy of mention has happened to a single battleship, nor yet to the cruisers or torpedo boats. You left this coast in a high state of battle efficiency and you return with your efficiency increased - better prepared than when you left, not only in personnel but even in material.![]() "As a war machine the fleet comes back in better shape than it went out. In addition you, the officers and men of this formidable fighting force, have shown yourselves the best of all possible ambassadors and heralds of peace. Wherever you have landed you have borne yourselves so as to make us at home proud of being your countrymen. You have shown that the best type of fighting man of the sea knows how to appear to the utmost possible advantage when his business is to behave himself on shore and to make a good impression on a foreign land.

"As a war machine the fleet comes back in better shape than it went out. In addition you, the officers and men of this formidable fighting force, have shown yourselves the best of all possible ambassadors and heralds of peace. Wherever you have landed you have borne yourselves so as to make us at home proud of being your countrymen. You have shown that the best type of fighting man of the sea knows how to appear to the utmost possible advantage when his business is to behave himself on shore and to make a good impression on a foreign land.![]() "We are proud of all the ships and all the men in this whole fleet, and we welcome you home to the country whose good repute among nations has been raised by what you have done."

"We are proud of all the ships and all the men in this whole fleet, and we welcome you home to the country whose good repute among nations has been raised by what you have done."

The Independent, Survey of the World,

Vol. LXVI, No. 3143, February 25, 1909

In my own judgment the most important service that I rendered to peace was the voyage of the battle fleet round the world.

Theodore Roosevelt,

in his Autobiography.

Post Card Published by Julius Bien in 1908

Was Embarrassment a Concern?

The Navy Department's first response to the news of the collision was:

![]() Navy Department officials at Washington say that the loss of the supplies [aboard the Republic] will not embarrass the fleet, as they were in the nature of an "extra shipment"[?] for use in the event of an emergency[?].

Navy Department officials at Washington say that the loss of the supplies [aboard the Republic] will not embarrass the fleet, as they were in the nature of an "extra shipment"[?] for use in the event of an emergency[?].

Brooklyn Union Standard, January 24, 1909, 6:2

Of course, there would have been a separate reason to conceal the Navy's payroll loss too - the Great White Fleet's round-the-world cruise was both a huge triumph for the United States and a great political success for Teddy Roosevelt, so why disclose something that would mar this historic event, even in the slightest?

FOOTNOTES

1The 25th of each month was a payday, infra, and was certainly, at least in general terms, an important date for the Paymaster. However, the Cunard Liner Carmania departed New York on schedule January 21, 1909 (N. Y. Herald, January 13, 09, 14:1), but was scheduled to arrive at Gibraltar on only January 28, 1909 (N. Y. Herald, European Edition, January 19, 09, 2:2). It is interesting to note that the Paymaster's emphasis is placed on the anticipated arrival of the Carmania "about" a payday. If Navy funds were lost aboard the Republic, and if, as a consequence, there were insufficient funds to meet, even belatedly, the January 25, 1909 payday (operational expenses would, no doubt, be met first), his planning might have been brought into question.

2The Russian Loan was originally scheduled to close on January 21, 1909, the same day the Carmania was scheduled to depart. See Footnote 1, supra. If the Russian gold was intended to be shipped to Russia via Gibraltar, but Russia had not received title until the loan closed, which occurred on January 22, 1909, this could be the explanation for the rescheduling of the US Navy's shipment. If the Republic carried a cargo for the Russian government and was to transfer this shipment to the Russian battleships then at Gibraltar, the off-loading of US Navy supplies at the same time would enhance (make less conspicuous) the security of the transfer.

3The Republic sank approximately 8:07 p.m. Eastern Time Sunday January 24, 1909. See Log of the Wreck. If the flagship at Villefranche, France (+ 6 hours) received a cablegram on "the afternoon of January 24 ... stating that the steamship Republic had that day sunk off Nantucket" that cablegram was either inaccurate or the Paymaster is incorrect in his recollection. Paymaster McGowan is most likely referring to the Navy Department, Bureau of Navigation's January 23, 1909 telegram to "Sperry, Connecticut, Villefranche" which stated: "Steamer Republic with provisions for fleet in collision and probably total loss Cannot be replaced from America" ... . NARA, RG 143, File 105669.

4Operations of Pay Department of the Atlantic Fleet on Cruise Around the World, Report of Pay Inspector Samuel McGowan, U. S. N. Fleet Paymaster. Presented by Mr. Perkins for Mr. Tillman, June 23, 1910, Congressional Serial 5660, 61st Congress 2nd Session, Senate Document No. 646, Page 47.

5Ibid. Page 99.

6Ibid. Page 100.

7Ibid. Page 99.

8Ibid. Page 101.

9All expenditures are computed from average Fleet expenditures at $12,367 per day as previously cited.

10Ibid. #4, Page 103.

11Loc. Cit.

12Ibid. #4, Page 107.

13An unspecified amount of British gold remained in the fleet upon its arrival in Hampton Roads (Ibid. Page 108). This money would probably not be used for disbursements after departure from Gibraltar (see II, supra) and, as a result, if no British gold were disbursed after departure from Gibraltar, the fleet's need for US gold would be greater than calculated.

14Ibid. #4, Page 99.

15Ibid. Page 98.

16Ibid. Page 104.

17Ibid. Page 105.

18 U.S. Navy Department. Information Relative to the Voyage of the United States Atlantic Fleet Around the World, December 16, 1907 to February 22, 1909. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1910, Itinerary, Pg 10.

19Log of the Voyage of the Atlantic Fleet, The Navy Publishing Company, Washington, DC, 1909, Pg 46.

20 Almost immediately after the loss of the Republic and her Government cargo, Fleet Paymaster McGowan acquired transport from the flagship, then at Villefranche, to Marseilles where he negotiated the provision of food stores sufficient for the Fleet to complete its cruise to Hampton Roads, in the amount of 247,060 francs ($47,682.58). The contract required the pay officers of the respective ships to pay upon delivery of the provisions "according to the prices hereinbefore stated, in French gold; provided, however, that payment for the provisions delivered to the U.S.S. GEORGIA, U.S.S. NEBRASKA, U.S.S. NEW JERSEY and U.S.S. RHODE ISLAND may be made in British gold at the American equivalent, (the pound sterling being worth $4.8665 and the franc being worth $0.193)." United States Atlantic Fleet, Contract for Fresh Meats and Fresh Vegetables at Marseille [sic], France, February 1, 1909, NARA RG 143, File 104151. This additional expenditure, too, is also NOT reflected within our analysis of the possibility of a loss of US Government funds; the funds expended for this purpose may have required replacement once the Fleet arrived at Hampton Roads and, therefore, may also be a part of the $800,000 delivered to the Fleet upon its arrival in the US.

21Ibid. #4 Page 109.

22Ibid. #18.

23N. Y. Sun, January 24, 09, 1:6. See also: #18, supra.

24Ibid #4, Page 105.

25Ibid. Page 108. It is also interesting to note that the Paymaster's commentary throughout his report is fairly specific, listing exact amounts and dates. However, at this point in his narration, the Paymaster is now "estimating." His report, too, although compiled by the Paymaster, was presented to the Senate by a second person - perhaps to avoid the possibility of a stray question.

26Yankton, Yacht and Man-Of-War, Malcolm F. Willoughby, Crimson Printing Company, Cambridge, MA, 1935, Pg 131.

27Ibid. #18, Itinerary of the USS Yankton, pg. 13.

28Ibid. #26, Pg 132.

29Logbook of the USS Yankton, NARA RG 24, pg. 234, 236.

30Ibid., pgs 240, 242. The Yankton's Logbook does not contain information regarding the distribution of the remaining 4 bags confidential mail or the $10,000 in gold. The Yankton most likely retained one secret code and some mail and funds for its operations.

31Ibid. #4, Page 108.

32Displacement, 975; Length, 185'; Beam, 27'6"; Draft, 13'10"; Speed, 14 knots; Complement, 78; Armament, six 3-pdrs., two Colt machine guns. For more information on USS Yankton, visit USS Yankton,