The Practically Unsinkable RepublicThe Republic, originally built as Dominion Line's Columbus, was launched in 1903 to that company's specifications, making her first trip across the Atlantic in October of that year. She was transferred shortly thereafter to the White Star Line.  The safety of the Dominion Line ships has been carefully looked after in every point. They all have double bottoms and many bulkheads by which the ship is divided into watertight compartments. These would positively prevent serious results in case of collision, as by them the water which might get into the ship is restricted to the one compartment injured - and even if several of these should be filled the boat could still proceed. The safety of the Dominion Line ships has been carefully looked after in every point. They all have double bottoms and many bulkheads by which the ship is divided into watertight compartments. These would positively prevent serious results in case of collision, as by them the water which might get into the ship is restricted to the one compartment injured - and even if several of these should be filled the boat could still proceed.

The Mediterranean Illustrated

Richards, Mills & Co. (Dominion Line), 1901, Pg 14. The Republic, just five years old, one of the most modern passenger liners afloat at that time, White Star Line's flagship of its Boston-Mediterranean service, was considered practically unsinkable. A ship of her size and modern-construction, with twelve watertight bulkheads, had never sunk before.  The Republic was built not only with an elaborate watertight compartment system, which generally reduces the danger of sinking in collision, but with a cellular double bottom, which makes her safer than many vessels of her time and class. She was as nearly unsinkable in theory as a vessel could be made when she was designed. The Republic was built not only with an elaborate watertight compartment system, which generally reduces the danger of sinking in collision, but with a cellular double bottom, which makes her safer than many vessels of her time and class. She was as nearly unsinkable in theory as a vessel could be made when she was designed.

New York Evening Sun, January 23, 1909, 2:2 ... She was designed as nearly unsinkable as a vessel could be made.

New York American, January 24, 1909, 4:4 … Her hull was extraordinarily strong in construction, being of the cellular double bottom type. There were eight watertight compartments, and in theory, at least, the ship was constructed so as to prove unsinkable.

New York Herald, January 24, 1909, 4:4 ... When she started from New York on her fatal trip, she was considered to be practically unsinkable by collision. So numerous were her compartments, so staunchly were her subdividing bulkheads built, that any qualified expert would have confidently asserted that two of her compartments might be flooded without sending the ship to the bottom. ... The Scientific American, February 6, 09, 110:1. Dr. Marsh, Republic's Ship's Surgeon, described the situation as the passengers, awakened from their slumber by the collision, were called on deck:  Captain Sealby came down from the bridge upon deck and spoke to a group of passengers standing near. "I do not think the ship will sink," he told them. "She may go down to a certain point, but it is likely her watertight compartments will keep her from sinking." He was given three cheers. Captain Sealby came down from the bridge upon deck and spoke to a group of passengers standing near. "I do not think the ship will sink," he told them. "She may go down to a certain point, but it is likely her watertight compartments will keep her from sinking." He was given three cheers.

N.Y. Herald, Jan. 26, 09, 4:4;

and Washington Evening Star, Jan. 25, 1909, 9:1. Shortly after the collision, Captain Sealby relayed the Republic's situation via the wireless to the White Star Line offices in New York.  It is declared by officers of the line in this city [New York] that there is no danger of the Republic sinking and that there will be no loss of life. It is declared by officers of the line in this city [New York] that there is no danger of the Republic sinking and that there will be no loss of life.

Trenton (New Jersey) Evening Times, January 23, 1909, 1:4 CAN FLOAT INDEFINITELY

The wireless reports from the vessels bound to the aid of the Republic were also quite heartening to the officers of the White Star line in this city. It appears that Capt. Sealby utilized his wireless apparatus solely for the purpose of sending out messages for help until he was assured that these messages had been heard and heeded. The wireless reports from the vessels bound to the aid of the Republic were also quite heartening to the officers of the White Star line in this city. It appears that Capt. Sealby utilized his wireless apparatus solely for the purpose of sending out messages for help until he was assured that these messages had been heard and heeded.

Then he bethought himself to make a wireless report to this office in New York. This report did not reach the White Star line until some time after the news had been given to the officials by The Evening World. Then he bethought himself to make a wireless report to this office in New York. This report did not reach the White Star line until some time after the news had been given to the officials by The Evening World.

There was a big sigh of relief in the White Star line offices when it became known that the Republic was still afloat and that La Lorraine and the Baltic were on their way to take off her passengers and crew should such a course be found necessary. It was stated for the line that the Republic, with her watertight compartments, would be able to keep afloat indefinitely with the engine room and boiler rooms flooded. But there was always danger of collision with another vessel, the Republic being no better as far as velocity and handling was concerned than a coal barge. There was a big sigh of relief in the White Star line offices when it became known that the Republic was still afloat and that La Lorraine and the Baltic were on their way to take off her passengers and crew should such a course be found necessary. It was stated for the line that the Republic, with her watertight compartments, would be able to keep afloat indefinitely with the engine room and boiler rooms flooded. But there was always danger of collision with another vessel, the Republic being no better as far as velocity and handling was concerned than a coal barge.

Evening World, January 23, 1909, 2:1.  [After issuing the wireless distress signal CQD, and establishing contact with other vessels in the vicinity,] Then messages were exchanged with the shore. Capt. Sealby got into communication with the White Star offices in this city [New York] notifying his owners of the accident, but conveying the welcome news that there was no danger to life, and that his vessel would float for some time at least. . . . [After issuing the wireless distress signal CQD, and establishing contact with other vessels in the vicinity,] Then messages were exchanged with the shore. Capt. Sealby got into communication with the White Star offices in this city [New York] notifying his owners of the accident, but conveying the welcome news that there was no danger to life, and that his vessel would float for some time at least. . . .

NY Times, Jan. 24, 09, 1:5  At midnight last night the news was received definitely at the White Star offices in Bowling Green that the Republic, while low in the sea and with a great hole in her starboard [should be port or left] side, was in no danger of sinking. At midnight last night the news was received definitely at the White Star offices in Bowling Green that the Republic, while low in the sea and with a great hole in her starboard [should be port or left] side, was in no danger of sinking.

New York Sun, January 24, 1909, 1:5. ... In the Company's office the experts got to work on the information and figured that even if six of the compartments were filled with water the vessel would still keep afloat and as the sea off Nantucket was very smooth the chances of saving her were very good indeed. ... N. Y. Sun, January 24, 09, 3:1  "While the Republic is seriously damaged, we have every hope of saving her. According to our figures, five or even six of the Republic's water-tight compartments might be flooded and she would still remain afloat. Capt. Sealby is one of the most competent commanders on the Atlantic, and we feel sure that he will not desert his vessel until the last hope of saving her has disappeared. …" "While the Republic is seriously damaged, we have every hope of saving her. According to our figures, five or even six of the Republic's water-tight compartments might be flooded and she would still remain afloat. Capt. Sealby is one of the most competent commanders on the Atlantic, and we feel sure that he will not desert his vessel until the last hope of saving her has disappeared. …"

Vice President P.A.S. Franklin, White Star Line

New York World, January 24, 1909, 2:5. [In the early afternoon of January 23, 1909, White Star Line had just issued its first official statement regarding the transfer of the Republic's passengers to the Florida.] In giving out the message that the Republic was still afloat Mr. Franklin said that it was the belief of the company that, as she remained afloat so many hours after she was struck, she would be kept from going down by her watertight compartments.

NY Times, Jan. 24, 09, 3:2  P. A. S. Franklin was of the opinion late yesterday afternoon that if the Republic had been kept afloat that long she would continue to float, and it would be possible to tow her into New York. [Emphasis supplied.] P. A. S. Franklin was of the opinion late yesterday afternoon that if the Republic had been kept afloat that long she would continue to float, and it would be possible to tow her into New York. [Emphasis supplied.]

New York Herald, January 24, 1909, 4:3 Captain Sealby, with, no doubt, advice from and after consultation with the Company's officials in New York, had found his ship still afloat 24 hours after the collision; he had every confidence that his ship would remain afloat and, therefore, could be saved.  At 1:40 yesterday afternoon the line received word that the derelict destroyer Seneca had located the Republic. "United States derelict destroyer Seneca reported twenty miles from the Republic," the message read, "and hastening toward her. With the aid of the vessel and the tugs Republic will be towed to New York." At 1:40 yesterday afternoon the line received word that the derelict destroyer Seneca had located the Republic. "United States derelict destroyer Seneca reported twenty miles from the Republic," the message read, "and hastening toward her. With the aid of the vessel and the tugs Republic will be towed to New York."

Officers of the company, in want of definite details concerning the condition of the Republic, declined to give any estimate as to the length of time which probably would be consumed in the journey. They were pleased to learn that the big liner was in a condition to be brought into port at all. [Emphases supplied.] Officers of the company, in want of definite details concerning the condition of the Republic, declined to give any estimate as to the length of time which probably would be consumed in the journey. They were pleased to learn that the big liner was in a condition to be brought into port at all. [Emphases supplied.]

New York Sun, January 25, 1909, 2:2. After transfer of the Republic's passengers to the Baltic,  Those of whom who were able to be up the next morning [January 24, 1909] had the mournful pleasure of seeing the crew return to their captain, who had never left the Republic, to wait until a tug should come to tow her, they hoped, as far as New York [Emphasis supplied.] , before a high sea could sink her. Those of whom who were able to be up the next morning [January 24, 1909] had the mournful pleasure of seeing the crew return to their captain, who had never left the Republic, to wait until a tug should come to tow her, they hoped, as far as New York [Emphasis supplied.] , before a high sea could sink her.

And as they cheered them off and the Baltic blew a long good-bye, they fell back in their deck chairs, vowing that never again should a journey start for them on a Friday. And as they cheered them off and the Baltic blew a long good-bye, they fell back in their deck chairs, vowing that never again should a journey start for them on a Friday.

[Republic passenger] Ruth Miller's Account, Pittsburgh Post, Jan. 26, 09, 2:1. Returns to Republic  And then this morning [about 10 a.m. Jan. 24], when the Republic was still afloat, and Captain Sealby went on board with two-score volunteers of his crew, Wireless Operator Binn [sic] returned with the rest. And then this morning [about 10 a.m. Jan. 24], when the Republic was still afloat, and Captain Sealby went on board with two-score volunteers of his crew, Wireless Operator Binn [sic] returned with the rest.

He brought with him storage batteries from the sister ship of the White Star line, the Baltic, and soon the delicate mechanism of the wireless apparatus had started to life under the magic influence of the electric spark. He brought with him storage batteries from the sister ship of the White Star line, the Baltic, and soon the delicate mechanism of the wireless apparatus had started to life under the magic influence of the electric spark.

To the sleepless, anxious operator [A. H. Ginman] in the little shack here at Siasconset there suddenly came again this morning the welcome call: "C K to S C," followed by this message: To the sleepless, anxious operator [A. H. Ginman] in the little shack here at Siasconset there suddenly came again this morning the welcome call: "C K to S C," followed by this message:

"Back at old stand. Waiting for Gresham to take us in tow. Hawser now coming aboard." "Back at old stand. Waiting for Gresham to take us in tow. Hawser now coming aboard."

As soon as he had written down the last word, Ginman flashed out the inquiry for further details. He could scarce believe the evidence of his own ears. Hours before he had received the Marconigram sent off to find its way through space to anxious hearts on shore, that the Republic was about to plunge beneath the waves, all passengers having been taken off by the disabled Florida and retransferred to the Baltic, where the crew also had found refuge. As soon as he had written down the last word, Ginman flashed out the inquiry for further details. He could scarce believe the evidence of his own ears. Hours before he had received the Marconigram sent off to find its way through space to anxious hearts on shore, that the Republic was about to plunge beneath the waves, all passengers having been taken off by the disabled Florida and retransferred to the Baltic, where the crew also had found refuge.

Again there was a clatter in the apparatus clamped about his head, and he heard: Again there was a clatter in the apparatus clamped about his head, and he heard:

Another Message  "Bulkheads still holding, and Republic may stay afloat indefinitely. Captain and 40 men aboard. Expect go New York. Have storage batteries brought aboard from Baltic." "Bulkheads still holding, and Republic may stay afloat indefinitely. Captain and 40 men aboard. Expect go New York. Have storage batteries brought aboard from Baltic."

... ...

Boston Post, Jan. 25, 09, 4:3. Sealby's Fight for His Ship  After the passengers had all been transferred to the Baltic, and safely transferred at that, though the odds had been all against the undertaking, and one or two persons had fallen overboard, but had been rescued, Capt. Sealby determined that the Republic was going to withstand the terrific battering she was getting from the waves and that, with care, she could be saved. He was on board again, and soon let Capt. Ranson of the Baltic know that he wanted back on board the members of the crew who had been taken to the Baltic. After the passengers had all been transferred to the Baltic, and safely transferred at that, though the odds had been all against the undertaking, and one or two persons had fallen overboard, but had been rescued, Capt. Sealby determined that the Republic was going to withstand the terrific battering she was getting from the waves and that, with care, she could be saved. He was on board again, and soon let Capt. Ranson of the Baltic know that he wanted back on board the members of the crew who had been taken to the Baltic.

Standing on the bridge of his damaged ship, confident and active still, though he had passed through twenty-four hours of experiences such as come to few men, and would try the sour of most, Capt. Sealby called through a megaphone to the Baltic, that he believed the Republic was going to stay afloat. Across the stretch of sea on the bridge of the Baltic stood Capt. Ranson. Standing on the bridge of his damaged ship, confident and active still, though he had passed through twenty-four hours of experiences such as come to few men, and would try the sour of most, Capt. Sealby called through a megaphone to the Baltic, that he believed the Republic was going to stay afloat. Across the stretch of sea on the bridge of the Baltic stood Capt. Ranson.

"Do you want us to continue to stand by?" asked Capt. Ranson through his megaphone, while the great crowd of passengers on the deck below, looked and listened and wondered. "Do you want us to continue to stand by?" asked Capt. Ranson through his megaphone, while the great crowd of passengers on the deck below, looked and listened and wondered.

Sealby's laugh could be heard across the water. "You can go on," he shouted. "We're all right." Sealby's laugh could be heard across the water. "You can go on," he shouted. "We're all right."

Then he went on to explain that it all depended on one bulkhead. If the bulkhead known as No. 1 held, all would be well. If it went, the shop [sic] would go, too. And Sealby yelled across the water that he believed the bulkhead was going to hold. Then he went on to explain that it all depended on one bulkhead. If the bulkhead known as No. 1 held, all would be well. If it went, the shop [sic] would go, too. And Sealby yelled across the water that he believed the bulkhead was going to hold.

There were standing by at this time the Anchor Line boat Furnessia and the revenue cutter Gresham, in addition to the Baltic. The New York, which had stood by for some hours and which it was expected would have to tow the Florida to New York, in all probability, was also in sight. There were standing by at this time the Anchor Line boat Furnessia and the revenue cutter Gresham, in addition to the Baltic. The New York, which had stood by for some hours and which it was expected would have to tow the Florida to New York, in all probability, was also in sight.

The Baltic Starts Homeward.  So it was that when Capt. Sealby announced that he was all right, the Baltic got under way for New York. ... So it was that when Capt. Sealby announced that he was all right, the Baltic got under way for New York. ...

Last of the Republic.  Back at the scene of the wreck Capt. Sealby was making good his promise to try and save his ship. With a small picked crew he was on the Republic, and the Gresham and the Furnessia had passed lines aboard in preparation for towing. The Furnessia was to act as a rudder, the lines being passed from he r bow to the stern of the Republic. The Gresham was dead ahead, trying to pull the disabled ship along. The whole intent was to get the Republic in shallow water along the Nantucket Shoals somewhere, so that if she sank something could be saved from the wreck. ... Back at the scene of the wreck Capt. Sealby was making good his promise to try and save his ship. With a small picked crew he was on the Republic, and the Gresham and the Furnessia had passed lines aboard in preparation for towing. The Furnessia was to act as a rudder, the lines being passed from he r bow to the stern of the Republic. The Gresham was dead ahead, trying to pull the disabled ship along. The whole intent was to get the Republic in shallow water along the Nantucket Shoals somewhere, so that if she sank something could be saved from the wreck. ...

NY Times, Jan. 26, 09, 2:1, 2 [Prior to the BALTIC's final departure, 10:45 a. m. Sunday...] Capt. Ranson reported that the Republic's engine rooms were flooded, that Hold No. 4 was full of water, that hold No. 3 was taking in the sea rapidly but that holds 1, 2, 5 and 6 were watertight. The ship appeared to be settling at that time and had a decided list to port [?]. The weather had remained favorable until that time and it seemed certain that the Republic was in no immediate danger of sinking. Before Capt. Ranson headed his ship toward this port Capt. Sealby asked that wrecking tugs be sent out to take care of his vessel, and Capt. Ranson, having communicated with his office here, informed Capt. Sealby that tugs were already on their way. ... Officials of the White Star Line had hoped to tow the Republic into port and take her direct to Erie Basin for temporary repairs. Afterwards she was to have been taken to Newport News to be patched up. N. Y. Sun, January 25, 09, 2:5 [Before the BALTIC bade her final departure...] Capt. Ranson held the Baltic near the Republic for two hours fearing that Capt. Sealby might need rescuing himself, but at 10 o'clock [a. m. Sunday, January 24], when Sealby seemed to think that he was safe enough and could keep his ship above water, the Baltic sounded a rousing good-by, dipped her colors and made tracks for New York. ... Captain Sealby's last actions aboard Republic indicate his impression that she would remain afloat. [Officer Williams, discussing his and Captain Sealby's last watch on the Republic] "You see everybody but the captain and myself had left the boat at 2 o'clock in the afternoon. About 6 o'clock I found my way below and carried up about sixteen biscuits, some marmalade, and a big hunk of plum cake. On this we had our dinner on the bridge. I also found some blankets and took them to the bridge, because we wanted to have things comfortable if she stood up all night. But that was fine plum cake." Globe and Commercial Advertiser, January 26, 1909, 2:2 N. Y. Sun, January 26, 09, :6 [Captain K.W. Perry of the Revenue Cutter Gresham, discusses the Republic's last moments,] "The Republic's watertight compartments had done such valiant service and she had remained drifting so many hours that Capt. Sealby actually believed she would hold her head above water until we towed her to a place of safety. He decided to stand by the bridge and took his blankets up there intending to snatch a little sleep after awhile if things went right, but he never got so much as a wink. ..."

New York Evening Sun January 25, 1909, 1:3, 4:6 And when the Baltic arrived in New York, Captain Ranson said: Evening World's Tug Gets

Capt. Ranson's Story at Sea Capt. Ranson's Story at Sea  As the Baltic halted off Ambrose Lightship [about 1:15 a.m. January 25, 1909], the tug Dalzeline, under charter by The Evening World, which had been waiting for her off the Hook all night, raced up alongside. From the deck of the dancing tug a reporter for this paper called up through a megaphone. As the Baltic halted off Ambrose Lightship [about 1:15 a.m. January 25, 1909], the tug Dalzeline, under charter by The Evening World, which had been waiting for her off the Hook all night, raced up alongside. From the deck of the dancing tug a reporter for this paper called up through a megaphone.

… …

[Capt. Ranson said,] "The condition of the Republic is favorable for salvage. She had no perceptible list when we parted from her, although she was well down by the stern." (At this time neither the Captain nor the reporter had any way of knowing that the Republic had gone down off Nantucket Island last night after a gallant effort by her crew to save her.) [Parenthetical comment in original.] [Capt. Ranson said,] "The condition of the Republic is favorable for salvage. She had no perceptible list when we parted from her, although she was well down by the stern." (At this time neither the Captain nor the reporter had any way of knowing that the Republic had gone down off Nantucket Island last night after a gallant effort by her crew to save her.) [Parenthetical comment in original.]

Evening World, January 25, 1909, 5:3;

Boston Daily Globe, January 25, 09, 1:5  [Delayed because of the fog,] There is some doubt whether the Gaspee [one of four tugs dispatched by White Star Line to assist Republic] will be able to get to the Republic, but as the disabled steamer was being towed along the sea side of Long Island very slowly there was a possibility that the Gaspee would overtake the Republic before she gets to the Narrows, the entrance to New York Harbor. [Emphasis supplied.] [Delayed because of the fog,] There is some doubt whether the Gaspee [one of four tugs dispatched by White Star Line to assist Republic] will be able to get to the Republic, but as the disabled steamer was being towed along the sea side of Long Island very slowly there was a possibility that the Gaspee would overtake the Republic before she gets to the Narrows, the entrance to New York Harbor. [Emphasis supplied.]

Providence Journal (RI), Jan. 25, 09, 2:5. At 8:15 p.m. on January 24, 1909, just minutes after the Republic had actually plunged beneath the waves, an as yet uninformed White Star Line issued the following statement to the press: The Merritt-Chapman Wrecking Company has sent down two large wrecking tugs to meet the Republic and to tow her to Erie Basin for temporary repairs. Thereafter she will be taken to the Government [!?] dry dock at Newport News for permanent repairs. New York Times, Jan. 25, 1909, 2  Until the word came from Capt. Sealby himself [received by White Star Line at 10:31 p.m. January 24, 1909, that the Republic had sunk] the steamship people believed that the Republic could be brought here in tow or beached. Bulletins which they received yesterday afternoon and last night said that the Republic's engine rooms were flooded, that one hold was full of water and another filling, but that she could keep afloat. Sealby's messages to his office indicated that he believed his ship could stay on top of the water. Until the word came from Capt. Sealby himself [received by White Star Line at 10:31 p.m. January 24, 1909, that the Republic had sunk] the steamship people believed that the Republic could be brought here in tow or beached. Bulletins which they received yesterday afternoon and last night said that the Republic's engine rooms were flooded, that one hold was full of water and another filling, but that she could keep afloat. Sealby's messages to his office indicated that he believed his ship could stay on top of the water.

New York Sun, January 25, 1909, 1:6. Sealby's Refusal of Assistance Captain Sealby's and White Star Line's knowledge of salvage law, and their informed belief that the Republic would remain afloat, that additional salvage tugs had already been dispatched to assist, that arrangements had been made to have her towed to Erie Basin for temporary repair (then from there she was to be taken to Newport News, Virginia, for permanent repair) - and the fact that the Republic did, indeed, sink while under tow - all account for Captain Sealby's continued refusal to accept, other than from vessels who could not claim a salvage award, the assistance of vessels who had arrived on the scene. Sealby accepted assistance from only the US Government's Revenue Cutters (who had a duty to assist), White Star Line's Baltic (the company could always assist itself) and Anchor Line's Furnessia.1 MARCONI OPERATORS

TELL THEIR STORY Two of Them Have A theory

That the Republic Could

Have Been Saved. THINK CAPT. SEALBY ERRED Say He Prefered to Wait for His Own

Tugs, and Declined Offers of Big

Ships to Beach Her.  Shortly after the steamships that stood by the Republic reached their piers yesterday their wireless operators hurried to the offices of the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company at 27 William Street and there made their official reports of the stirring events of the last three days. Among them were the operators of the New York, the Lucania, and the Furnessia. The first two unhesitantly asserted that the Republic could have been saved had Capt. Sealby accepted the proffers of aid made to him by the Captains of the ships that surrounded him. He refused the help proffered, they said, and thus the precious time left in which to save the stricken ship slipped by. Then when the tugs sent by the White Star Line arrived it was too late. Shortly after the steamships that stood by the Republic reached their piers yesterday their wireless operators hurried to the offices of the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company at 27 William Street and there made their official reports of the stirring events of the last three days. Among them were the operators of the New York, the Lucania, and the Furnessia. The first two unhesitantly asserted that the Republic could have been saved had Capt. Sealby accepted the proffers of aid made to him by the Captains of the ships that surrounded him. He refused the help proffered, they said, and thus the precious time left in which to save the stricken ship slipped by. Then when the tugs sent by the White Star Line arrived it was too late.

F. P. W. Allen, the New York's operator, said shortly after the New York found the Republic and the fog had lifted sufficiently to permit of the New York getting alongside, Capt. Roberts of the New York shouted through his megaphone to Capt. Sealby that shallow water was only a few miles distant, and that he would willingly tow the Republic where she could be beached if Capt. Sealby so wished. According to Allen, Capt. Sealby shouted back that he intended to wait for the tugs that were being rushed to him by the White Star Line, and that he would have to decline all offers of aid. F. P. W. Allen, the New York's operator, said shortly after the New York found the Republic and the fog had lifted sufficiently to permit of the New York getting alongside, Capt. Roberts of the New York shouted through his megaphone to Capt. Sealby that shallow water was only a few miles distant, and that he would willingly tow the Republic where she could be beached if Capt. Sealby so wished. According to Allen, Capt. Sealby shouted back that he intended to wait for the tugs that were being rushed to him by the White Star Line, and that he would have to decline all offers of aid.

"If Capt. Sealby had accepted our offer the Republic would be resting in shallow water now, and the loss would be trivial," Allen said: "but I suppose he knew what he was about." "If Capt. Sealby had accepted our offer the Republic would be resting in shallow water now, and the loss would be trivial," Allen said: "but I suppose he knew what he was about."

Frank Lloyd, the wireless operator of the Lucania, coincided with the views of Allen, and added that the Captain of his ship also had offered to tow the Republic to shallow water, but that Capt. Sealby had declined to allow him to do so. Frank Lloyd, the wireless operator of the Lucania, coincided with the views of Allen, and added that the Captain of his ship also had offered to tow the Republic to shallow water, but that Capt. Sealby had declined to allow him to do so.

. . .

NY Times, Jan. 26, 09, 4:5 … On coming near the Republic [at approximately 8 p.m. January 23, 1909] Capt. Fenlon sent a boat in charge of the chief officer alongside the White Star boat with offers of assistance.

Capt. Fenlon, who is familiar with he waters about Nantucket, said he was sure he could tow the vessel to Newport or beach her in shoal water before she filled. Capt. Fenlon, who is familiar with he waters about Nantucket, said he was sure he could tow the vessel to Newport or beach her in shoal water before she filled.

The offer of assistance was refused by Capt. Sealby, who said that tugboats were already on their way to him. Capt. Sealby seemed anxious about the Florida and suggested that the City of Everett go to the assistance of the Italian vessel. The oil ship stood by all night and then proceeded for New York, where she was bound from Boston. The offer of assistance was refused by Capt. Sealby, who said that tugboats were already on their way to him. Capt. Sealby seemed anxious about the Florida and suggested that the City of Everett go to the assistance of the Italian vessel. The oil ship stood by all night and then proceeded for New York, where she was bound from Boston.

It was suggested that Capt. Sealby, thinking that tugs would reach him, did not wish to take chances on salvage. ... It was suggested that Capt. Sealby, thinking that tugs would reach him, did not wish to take chances on salvage. ... New York Evening Sun, January 27, 1909, 1:5  Developments last night indicated that the Republic could have been saved if the captain had accepted the offer of the captain of the Standard Oil Trust's steamer City of Everett. Developments last night indicated that the Republic could have been saved if the captain had accepted the offer of the captain of the Standard Oil Trust's steamer City of Everett.

The report of the Standard Oil skipper was forwarded yesterday to the officials of the International Mercantile Marine Company. In that report the oil company's captain said his was the first of the relief boats to come up with the Republic. With the powerful pumps he had aboard, he added, he could have saved the disabled steamship and towed her to port. The captain, however, declined his offer for fear of salvage charges and relied on two government vessels which the wireless told him were on the way. The report of the Standard Oil skipper was forwarded yesterday to the officials of the International Mercantile Marine Company. In that report the oil company's captain said his was the first of the relief boats to come up with the Republic. With the powerful pumps he had aboard, he added, he could have saved the disabled steamship and towed her to port. The captain, however, declined his offer for fear of salvage charges and relied on two government vessels which the wireless told him were on the way.

New York American, January 28, 1909, 3:1

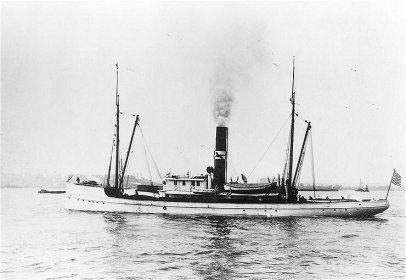

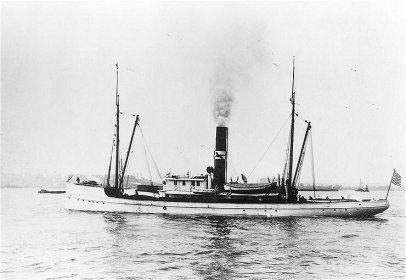

Merritt & Chapman Salvage Tug Relief2

(Notice Black Horse logo on stack.) Sealby's Refusal of a Tow.  The unwritten law in the marine world that the Captain is the supreme commander of his vessel when she is at sea will not be modified by the fact that the wireless system keeps him in almost constant touch with his owners ashore. For this reason it is probable that Capt. Sealby's refusal to allow the City of Everett to tow him will not be questioned. His first duty was to insure the safety of his passengers, and this he had fulfilled when they were put aboard the damaged Florida. He had the right to use his own judgment afterward, and in refusing a tow he had the knowledge that the company had sent out to help him the wrecking steamer Relief, the Government cutters, and several sea-going tugs. . . . The unwritten law in the marine world that the Captain is the supreme commander of his vessel when she is at sea will not be modified by the fact that the wireless system keeps him in almost constant touch with his owners ashore. For this reason it is probable that Capt. Sealby's refusal to allow the City of Everett to tow him will not be questioned. His first duty was to insure the safety of his passengers, and this he had fulfilled when they were put aboard the damaged Florida. He had the right to use his own judgment afterward, and in refusing a tow he had the knowledge that the company had sent out to help him the wrecking steamer Relief, the Government cutters, and several sea-going tugs. . . .

NY Times, Jan. 28, 09, 2:3

See also NY Times, Jan. 27, 09, 1:5, which

describes the City of Everetts' offer of assistance. Capt. Sealby may have had an additional reason to refuse all offers of assistance other than from those parties who could not claim a salvage award. Under the terms of White Star Line's Bill of Lading, under which White Star Line accepted and transported cargo: In case of salvage services rendered to aforesaid merchandise or treasure [Yes, it really says that!] during the voyage by a vessel of the same line, such salvage services shall be paid for as fully as if such salving vessel or vessels belonged to strangers. ... General Average payable according to York-Antwerp Rules. . . . NARA, RG 143, 105669. By waiting for Company vessels, Capt. Sealby would have saved White Star line the expense of paying third parties their salvage claims, and, under the terms of its Bills of Lading, White Star line may have been able to acquire additional revenues from those who shipped cargo aboard Republic to, at least, offset its expenses. Under the salvage concept of General Average - also a term within White Star line's Bill of Lading - the cargo owners would have been required to contribute their proportionate share of the salvage expenses as the value of their cargo bears to the total value of the salvaged vessel and cargo.3 Sealby Stayed with His Ship to the Last. Although the Baltic's Capt. Ranson provides a romanticized explanation, below, for why Capt. Sealby stayed with his ship at all times while she remained afloat, and only left her as she sank beneath him, Capt. Sealby's reasons for staying at his post were probably more practical: 1. he didn't believe his ship would sink; and, 2. if he had left the ship while afloat, someone might have boarded her, saved her, and, as a result, claimed her under salvage law as a salvage prize.  You may ask why Captain Sealby felt that he must stick by his ship even at great personal risk. It is true that he and his second officer were the only ones on board when the Republic finally foundered, and were thrown into the sea and rescued with some difficulty on account of the darkness. They ran this risk, not in the least to indulge in pyrotechnics, for Captain Sealby is not that kind of man, but for two very good reasons. First, it is a tradition of the sea that a Captain must stick to his ship until the last hope is gone, and that he must be the last one to leave her. In the second place, if he should abandon his ship even with the conviction that she was hopelessly lost, and then some other vessel or seamen should come along and save her, his own judgment could very easily be questioned, and his reputation as a resourceful and trustworthy commander would be irretrievably ruined. . . . You may ask why Captain Sealby felt that he must stick by his ship even at great personal risk. It is true that he and his second officer were the only ones on board when the Republic finally foundered, and were thrown into the sea and rescued with some difficulty on account of the darkness. They ran this risk, not in the least to indulge in pyrotechnics, for Captain Sealby is not that kind of man, but for two very good reasons. First, it is a tradition of the sea that a Captain must stick to his ship until the last hope is gone, and that he must be the last one to leave her. In the second place, if he should abandon his ship even with the conviction that she was hopelessly lost, and then some other vessel or seamen should come along and save her, his own judgment could very easily be questioned, and his reputation as a resourceful and trustworthy commander would be irretrievably ruined. . . .

THE TRIUMPH OF WIRELESS, by Capt. Ranson

The Outlook, Feb. 6, 09, 297. But, The Republic Ultimately Foundered, and

The Explanation for the Loss. … Underwriters who discussed the disaster yesterday put some of the blame for the loss of the steamship on the wrecking companies. The wrecking tug Relief was in this harbor, but her captain declined to go to sea in such a thick fog. Had the Relief been able to get to the Republic with her powerful pumps it is thought she could have kept the vessel afloat. Boston Evening Transcript, January 26, 1909, 3:4. . WHITE STAR LINE WILL

TRY TO RAISE REPUBLIC Special Dispatch to the EVENING NEWS.

NEW YORK, Jan. 25 - The first news of the sinking of the Republic was received by the White Star Line Company in the city at 10:31 o'clock and was a dispatch from Captain Sealby himself.

"Republic sunk. All lives saved. Making Gray [sic, should be Gay] Head on the Gresham." "Republic sunk. All lives saved. Making Gray [sic, should be Gay] Head on the Gresham."

Until this message came from Captain Sealby the officials of the White Star Line believed the vessel could be towed to some port and would be saved. Bulletins received last night said the Republic's engines were flooded; that one hold was full of water and another filling, but that she could be kept afloat. Until this message came from Captain Sealby the officials of the White Star Line believed the vessel could be towed to some port and would be saved. Bulletins received last night said the Republic's engines were flooded; that one hold was full of water and another filling, but that she could be kept afloat.

One report was that the Republic had gone down in forty-five fathoms of water. A second message said she had sunk in thirty fathoms - both pretty deep to attempt salvage - but an attempt will be made at once to raise the big vessel. One report was that the Republic had gone down in forty-five fathoms of water. A second message said she had sunk in thirty fathoms - both pretty deep to attempt salvage - but an attempt will be made at once to raise the big vessel.

This attempt is expected to be made as soon as the weather clears. This attempt is expected to be made as soon as the weather clears.

David Lindsey, general agent of the White Star Line, blames the failure of tugboats to respond to the call for help from the Republic for the sinking of the vessel. David Lindsey, general agent of the White Star Line, blames the failure of tugboats to respond to the call for help from the Republic for the sinking of the vessel. Newark [NJ] Evening News, Jan. 25, 09, 3:2,3. BLAMES TUGS FOR SHIP'S LOSS  David Lindsey, general passenger agent of the White Star line, said yesterday that every effort was made Saturday night to get tugs from Boston and other places along the shore line to go out in the fog to the aid of the Republic. The tugs would not venture out, he said, and he declares that if they had gone the Republic would have been towed into more shallow water and eventually saved. N.Y. Herald, Jan. 25, 09. 4:2.  The sinking of the Republic made useless the voyage of four large tugs which had started for the Republic, the Underwriter from Boston, the John Scully and the Gaspee from Providence, and the Relief from New York. The sinking of the Republic made useless the voyage of four large tugs which had started for the Republic, the Underwriter from Boston, the John Scully and the Gaspee from Providence, and the Relief from New York.

Until the word [of the Republic's loss] came from Capt. Sealby himself, the steamship people believed the Republic could be brought here in tow or beached. Bulletins which they received this afternoon and tonight said that the Republic's engine room were flooded, that one hold was full of water and another filling, but that it could keep afloat. Sealby's messages to his office indicated that he believed his ship could stay on top of the water. [Emphasis supplied.] Until the word [of the Republic's loss] came from Capt. Sealby himself, the steamship people believed the Republic could be brought here in tow or beached. Bulletins which they received this afternoon and tonight said that the Republic's engine room were flooded, that one hold was full of water and another filling, but that it could keep afloat. Sealby's messages to his office indicated that he believed his ship could stay on top of the water. [Emphasis supplied.]

New York Sun, Jan. 25, 1909, 1:6; and

Chicago Daily Tribune, Jan. 25, 09, 1:7.  It was stated at the White Star Line offices to-day that the Republic would be a total loss. Had the weather been clear Saturday two wrecking tugs sent out would have been able to reach the wrecked ship and kept her from going down, but the fog which delayed the rescuers doomed the big steamer. It was stated at the White Star Line offices to-day that the Republic would be a total loss. Had the weather been clear Saturday two wrecking tugs sent out would have been able to reach the wrecked ship and kept her from going down, but the fog which delayed the rescuers doomed the big steamer.

Brooklyn Times, January 25, 1909, 1:1 Fog Blamed for Loss of Ship.  The fog which was the cause of the accident yesterday morning was to blame for the loss of their ship, the White Star people were certain. Had it lifted so the tugs hustled out to sea could have got to the side of the Republic they could have kept it above water. The fog which was the cause of the accident yesterday morning was to blame for the loss of their ship, the White Star people were certain. Had it lifted so the tugs hustled out to sea could have got to the side of the Republic they could have kept it above water.

New York Sun, Jan. 25, 09, 1:6; and

Chicago Daily Tribune, Jan. 25, 09, 2:1. Indeed, the Republic's demise came as a surprise to most. DELAY OF WRECKING TUGS. Fog and Other Drawbacks Prevented

Their Arriving on Time  The question having arisen as to why assistance did not reach the White Star liner Republic in time to keep her from sinking, investigation yesterday brought out the fact that only an unfortunate combination of circumstances, in which the dense fog of Saturday and Sunday played a prominent part, prevented her from being brought safely into port. The question having arisen as to why assistance did not reach the White Star liner Republic in time to keep her from sinking, investigation yesterday brought out the fact that only an unfortunate combination of circumstances, in which the dense fog of Saturday and Sunday played a prominent part, prevented her from being brought safely into port.

Everything seemed to be against the work of rescue, and the Relief1, the powerful deep-sea salvage boat of the Merritt & Chapman Wrecking Company, which was the first to start to the aid of the Republic, did not arrive off the Nantucket Shoals until nearly ten hours after the ship had gone down. John Lee, Vice President of the White Star Line, said last night at his home in Brooklyn that he is firmly convinced that had the Relief got to the Republic in time things would have been different. The Merritt & Chapman boat is fitted with powerful pumps and is considered as one of the best-equipped salvage boats afloat. She was to have been assisted in the rescue of the Republic by three or four other wrecking boats, but none of them could reach the steamer. Everything seemed to be against the work of rescue, and the Relief1, the powerful deep-sea salvage boat of the Merritt & Chapman Wrecking Company, which was the first to start to the aid of the Republic, did not arrive off the Nantucket Shoals until nearly ten hours after the ship had gone down. John Lee, Vice President of the White Star Line, said last night at his home in Brooklyn that he is firmly convinced that had the Relief got to the Republic in time things would have been different. The Merritt & Chapman boat is fitted with powerful pumps and is considered as one of the best-equipped salvage boats afloat. She was to have been assisted in the rescue of the Republic by three or four other wrecking boats, but none of them could reach the steamer.

Thought Republic Would Not Sink.

All of the various boats that passed the Republic during the twenty-four hours after the accident reported that she was riding in good shape, and none of them expressed any fear that she would go down. Capt. Ranson of the Baltic sent a wireless message to the officials of the line as he came up the bay Sunday night, saying that the chief engineer of the Republic had reported to him that the leaks through the engine room bulkheads of the injured boat were such as could be remedied by a couple of strong pumps, and that only the one big break into the engine room at the point where the prow of the Florida struck the side would need outside treatment. Curiously, this message was not received until after the boat had sunk, and the men on the Baltic were much surprised to learn when they reached the pier on Monday morning that the Republic had gone down. The Standard Oil steamer City of Everett sent a wireless message ashore as she entered the bay at midnight Sunday, that she had passed the Republic earlier in the day, and that she was in good condition and in no immediate danger. This was hours after the ship had sunk. All of the various boats that passed the Republic during the twenty-four hours after the accident reported that she was riding in good shape, and none of them expressed any fear that she would go down. Capt. Ranson of the Baltic sent a wireless message to the officials of the line as he came up the bay Sunday night, saying that the chief engineer of the Republic had reported to him that the leaks through the engine room bulkheads of the injured boat were such as could be remedied by a couple of strong pumps, and that only the one big break into the engine room at the point where the prow of the Florida struck the side would need outside treatment. Curiously, this message was not received until after the boat had sunk, and the men on the Baltic were much surprised to learn when they reached the pier on Monday morning that the Republic had gone down. The Standard Oil steamer City of Everett sent a wireless message ashore as she entered the bay at midnight Sunday, that she had passed the Republic earlier in the day, and that she was in good condition and in no immediate danger. This was hours after the ship had sunk.

NY Times, Jan 27, 09, 2:5 Even the crew of the Gresham were surprised at her sudden loss.  WOODS HOLE, Mass. Monday. - The revenue cutter Gresham, Captain Perry, which had been in constant attention on the steamship Republic, which sank last night in Nantucket Sound, arrived in this harbor at eleven o'clock to-day. The crew of the Gresham, though tired out, told of the thrilling experiences in succoring the passengers and crew of the ill fated steamship. WOODS HOLE, Mass. Monday. - The revenue cutter Gresham, Captain Perry, which had been in constant attention on the steamship Republic, which sank last night in Nantucket Sound, arrived in this harbor at eleven o'clock to-day. The crew of the Gresham, though tired out, told of the thrilling experiences in succoring the passengers and crew of the ill fated steamship.

The hours after the crash of the Florida had been of intense anxiety to all of the people who had hurried out there, but the last few seconds were the climax for, within two minutes after the first real suspicion that the government cutters were not going to be able to save the ship, the magnificent hull and cargo sank into the sea at a depth which precludes the possibility of ever saving her or the cargo, which, included with the ship, will cause a loss of more than $1,750,000. The hours after the crash of the Florida had been of intense anxiety to all of the people who had hurried out there, but the last few seconds were the climax for, within two minutes after the first real suspicion that the government cutters were not going to be able to save the ship, the magnificent hull and cargo sank into the sea at a depth which precludes the possibility of ever saving her or the cargo, which, included with the ship, will cause a loss of more than $1,750,000.

... ...

... The Gresham's officers say that the final loss of the ship was a great surprise to all concerned, as, when they began towing her yesterday, Captain Perry, who has had large experience in towing disabled ships, said the trip would probably end successfully. But the end came suddenly and cut out all calculations. [Emphasis supplied.] ... The Gresham's officers say that the final loss of the ship was a great surprise to all concerned, as, when they began towing her yesterday, Captain Perry, who has had large experience in towing disabled ships, said the trip would probably end successfully. But the end came suddenly and cut out all calculations. [Emphasis supplied.]

... ...

Evening Telegram, January 25, 1909, 3:6 & 7 Now, we can turn our attention to the rescue, or loss, of the Republic's cargos. | |